La révolution banale

Talking as if time matters when it comes to understanding generative AI

These are notes for a talk I gave at the Explorance French Europe Summit in October, and updated for a talk at the Explorance Europe Summit in November. The words here approximate what I said but my talks are looser and more interactive than the notes capture.

The images here are screenshots from Prezi, which is my preferred presentation tool. I provide links to references and image credits here so interested audience members can find them.

I pulled together recent thoughts on chatbots and use of large AI models in higher education to talk about generative AI as analogous to technologies that once felt dangerous and exciting, but today feel ordinary, normal, banal, even boring. This talk was originally called The Boring Revolution but just about everything, it sounds cooler in French.

One weird thing about transformer-based AI models is that most of us access them through an interface that is over fifty years old. This new-wine-in-old-bottles aspect to ChatGPT makes it difficult to understand the potential of the technology and use it for new purposes. We anthropomorphize it as a companion, a co-intelligence, a helpful intern, when in fact, it is powerful new cultural technology, best understood as language machines. We are only beginning to understand what they can do.

To call AI banal or normal is to call attention to historical processes that are shaping how it is being developed and diffused, countering the hype created by those who speculate wildly about its potential, usually to sell something. Like all inventions, including the dynamo, the internal combustion engine, and the open-stack library, AI technology will take a while to be incorporated meaningfully into our work and lives. Autonomous vehicles are an example of an AI technology that seems about to pass a threshold that will soon make it feel as ordinary as your public library or the street light outside your house.

Will that happen with generative AI? Of course it will, though we cannot know when or how things will play out. But doesn’t it seem like ChatGPT is already beginning to feel like la révolution banale?

I begin by asking the audience to apply the duck/rabbit image made famous (for philosophers) by Ludwig Wittgenstein to how we first saw generative AI. In those early days, ChatGPT was seen as either the Duck of Doom or the Rabbit of Glad Tidings. Today, most see it as double-edged, both a duck and a rabbit, as having the potential to be beneficial and harmful.

Then we talk about the fact that the people who released ChatGPT in late 2022 did so as an experiment, a way to gather user data. They were as surprised as everyone else at the result: the creation of what is often described as the fastest-growing computer application in history.

Then we compare the interface of Eliza, one of the earliest chatbots…

to ChatGPT’s interface. Pretty much the same.

The key terms for the talk are:

Natural language capabilities of generative AI have a much greater range of applications than simulating conversation.

Generative AI may be a general purpose technology but it can be used for specific purposes and narrowly defined tasks, including search within platforms and analysis of unstructured datasets.

Orchestrating various AI models built for different purposes and re-engineering academic and business processes (workflows) to use AI will be harder and more important than figuring out how chatty companions can help individual knowledge workers.

I use this article from The Markup to explain how organizations are using natural language search to manage information. AI. Neutron Enterprise, a large language model developed by Atomic Canyon, is not deciding anything. It is not even summarizing the millions of pages of regulations and compliance guidance employees are reviewing in order to extend Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant through 2029. All the AI model is doing is finding the relevant regulations and guidance for each decision the workers have to make, so the workers themselves can interpret the rules.

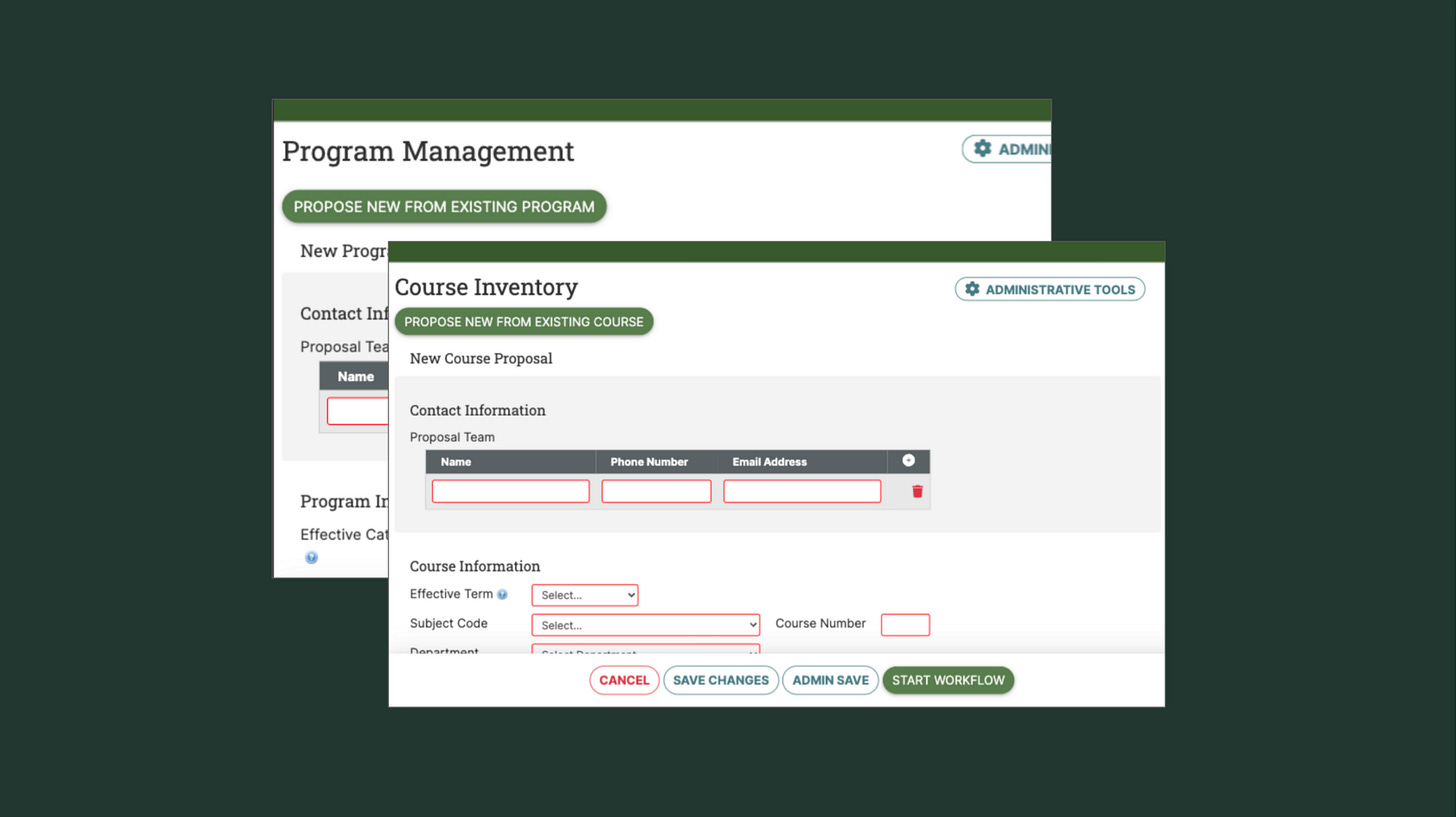

My favorite example from higher education, is a natural language search feature developed by Courseleaf, a platform that manages academic processes like course rostering, registration, and academic planning. One of their modules is Curriculum Manager. This is a system faculty members use to propose new courses, and administrators use to manage the curriculum review and approval process. Natural language search allows faculty proposing new courses and programs, and deans reviewing those proposals, a better understanding of similar courses and programs being offered.

The event is sponsored by Explorance, so the audience will see demonstrations of MLY, their AI model, in action. It is a purpose-built model for analyzing student comment data gathered through course evaluations. For more on MLY, see this section of my essay On Beyond Chatbots.

In all my talks, I plug my favorite purpose-built technology for understanding complex ideas: books.

Specifically, I recommend the book AI Snake Oil. The authors, Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, write one of the best AI newsletters. Their new book project, AI as normal technology, and their relaunched newsletter under the same name, offer an alternative to the hype about imminent superintelligence and predictions of an immediate transformation of work and education. Treating generative AI as normal technology focuses our attention on the social processes of adopting this new social technology rather than speculation about the unknowable future it may bring. I use their framework as a way to think beyond the chatbot and about the history of technology going back much further than the last three years.

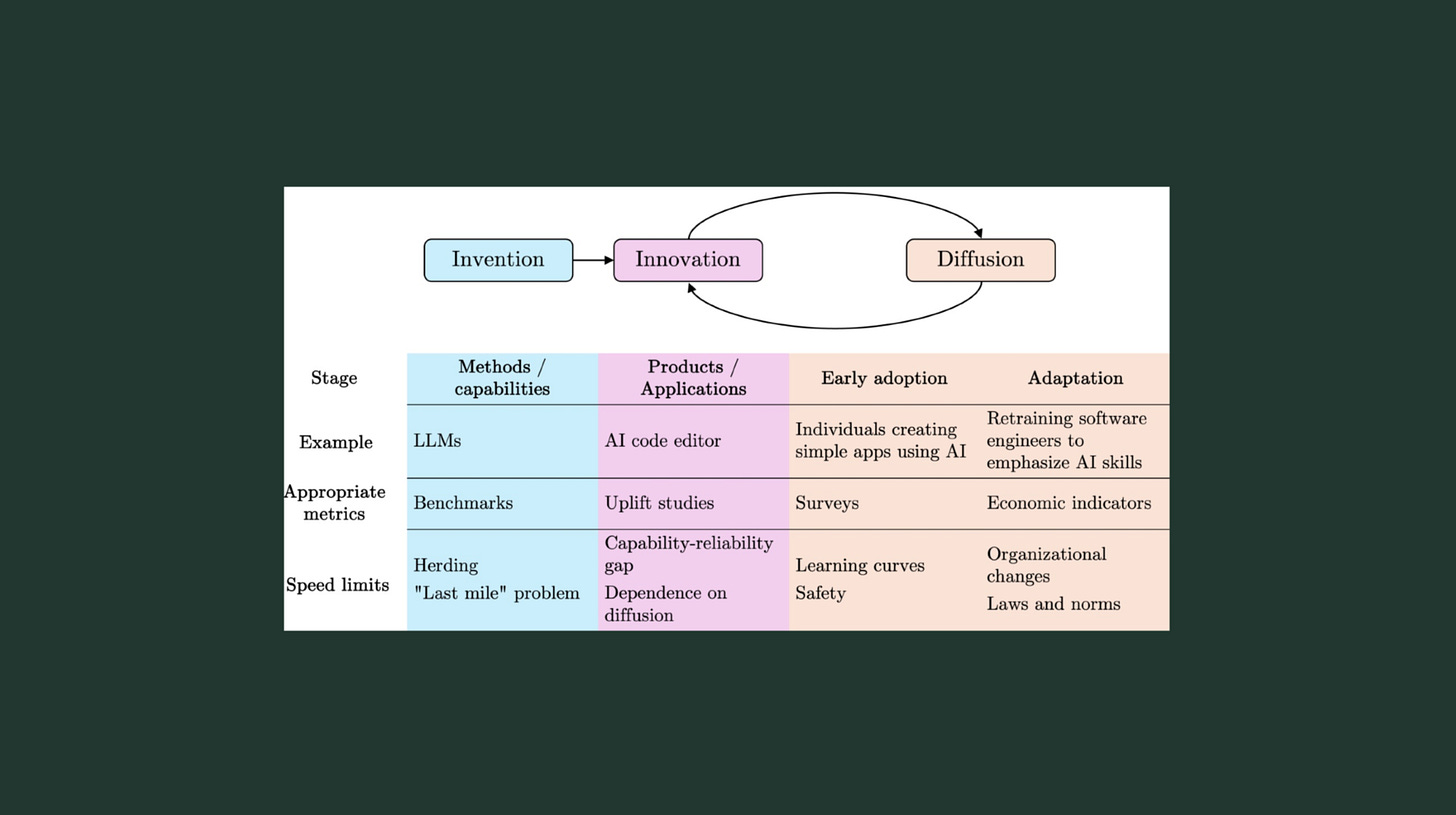

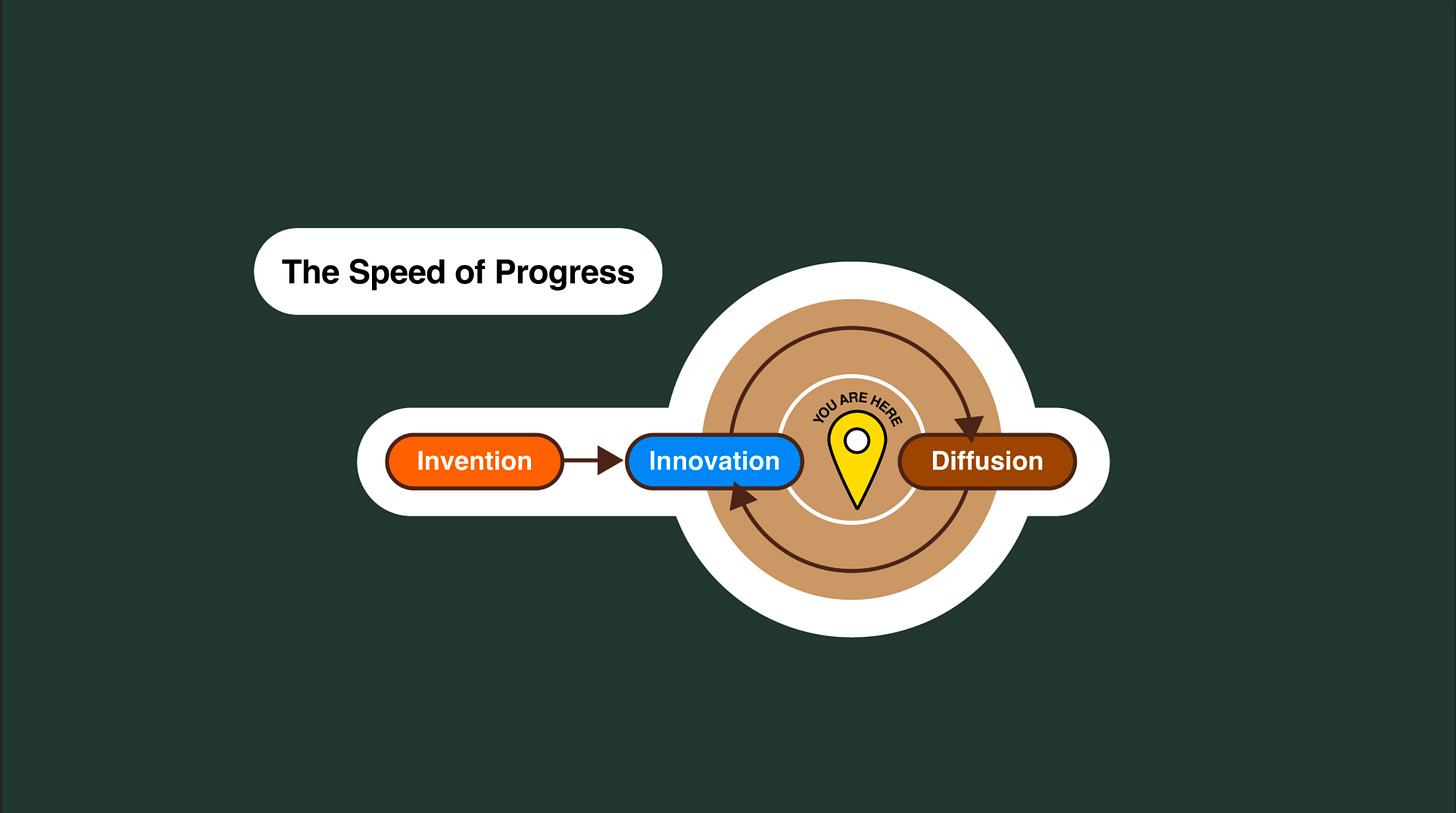

I talk about how we focus on the invention of technologies and downplay the historical processes of innovation and diffusion. There are speed limits in each part of the cycle. Pay particular attention to diffusion, the peach-colored area.

The speed of progress happens at the speed of humans and institutions. Electricity, the internal combustion engine, and the electronic computer all took decades to understand, to innovate, and to commercialize. Those technologies didn’t feel normal when they were invented; they became normal through social processes of adaptation and adoption. Generative AI will be no different.

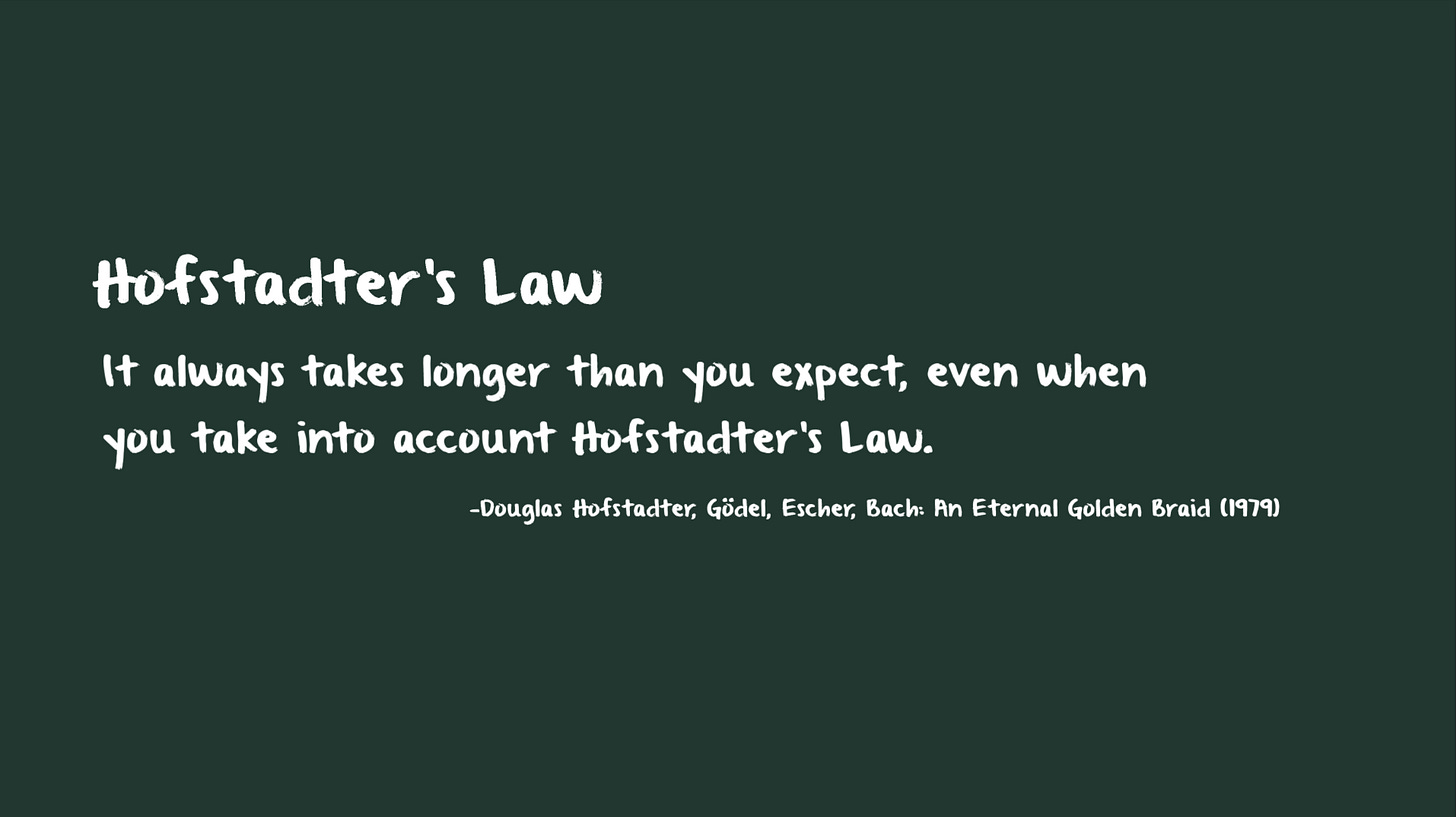

This leads me to my favorite “law,” which is about AI but applies to so much more in software development and in life.

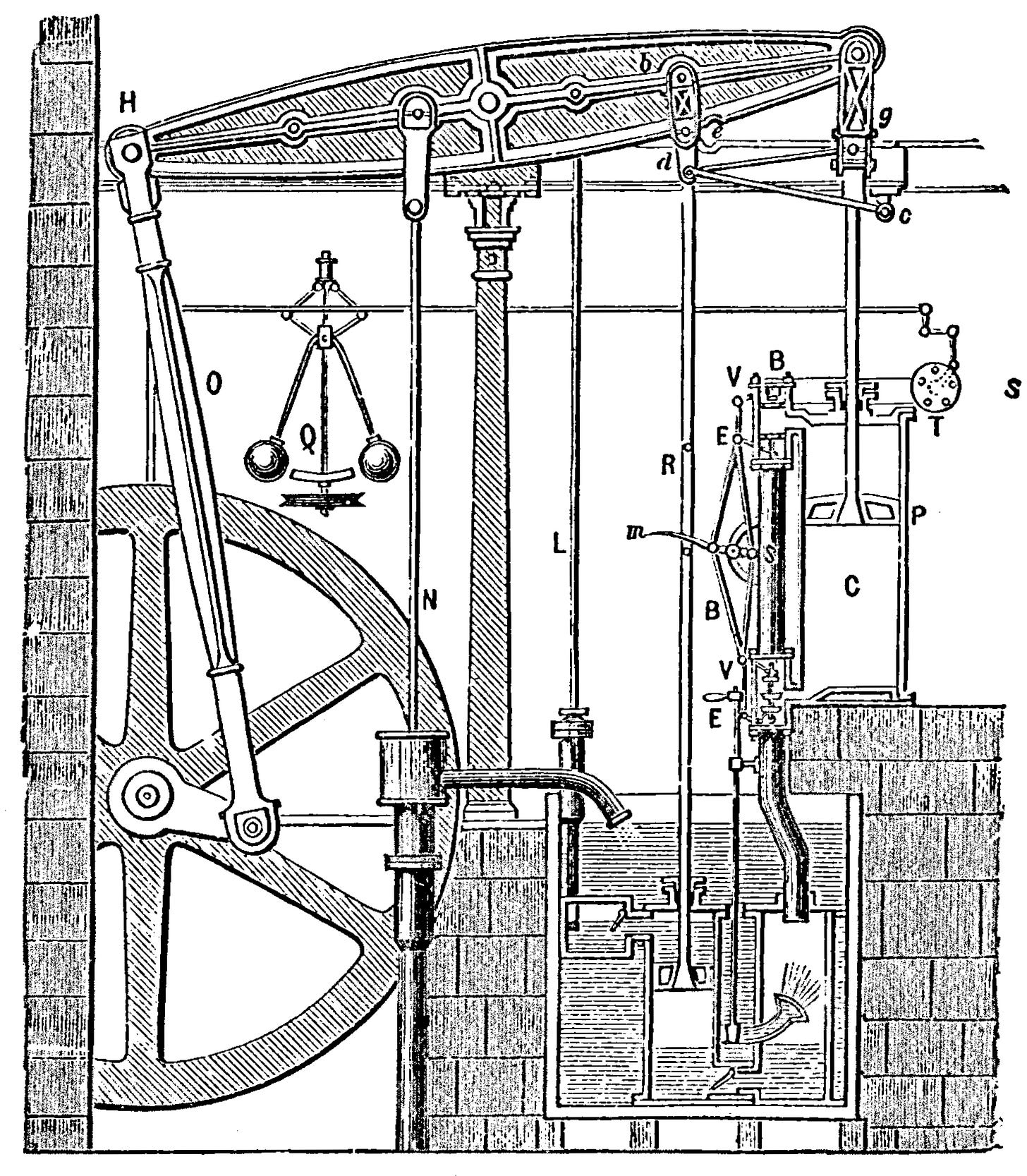

The talk in Edinburgh was at The National Robotarium at Heriot Watt University. When I was in school, I learned James Watt invented the steam engine.

Now that’s not true, and just like the transformer—the “T” in GPT that is the key invention for recent large language models—and the processes used to pre-train the models, there is no single inventor of a general purpose technology.

I really hope that schoolchildren a hundred years from now are not told Sam Altman invented ChatGPT.

What James Watt did in the 1760s was innovate on a technology that was developed about fifty years earlier. Watt’s innovations allowed steam engines to be used for many new purposes. In the decades that followed, other innovators improved and adapted steam engines, resulting in railroad locomotives and steam ships, and powerful new manufacturing machines.

Then, just as steam was starting to feel a bit boring, an exciting new technology appeared. In the following decades, generating electricity became a lot less exciting. Think about all the boring tools we take for granted that are enabled by electrification. Indoor lighting, toaster ovens, household machines that clean our dishes and our clothes....

All that is based on the wild and crazy idea that we could generate that scary naturally occurring phenomenon known as lightning, and direct it into your house using wires.

Think about how dangerous and revolutionary that sounded to any normal person in 1880.

You can tell the story of electrification as a fight between big personalities with George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison as the Sam Altman and Elon Musk of the 1890s. You can also tell it as a boring story of patent lawsuits and corporate mergers.

Here is my version, and the protagonists are not inventors, entrepreneurs, or corporate lawyers.

My heroes are the innovators and diffusers. The people who worked for those early electric companies, the people who tinkered with light bulbs and lighting systems in their workshop or backyard. The local planners and residents who worked to light their cities and towns. The regulators and government officials who made it work on a national scale. The engineers who decided where to build power plants and the clerks who figured out how to bill customers. The people who solved all the little challenges of stringing electrical wires across the continent and connecting them to homes and businesses.

They slowed things down by asking questions, proposing alternatives, and listening to each other. To be sure, there were mistakes and problems, fires and accidental deaths. It took years of innovation to make sure we could safely light city streets and send power directly into homes.

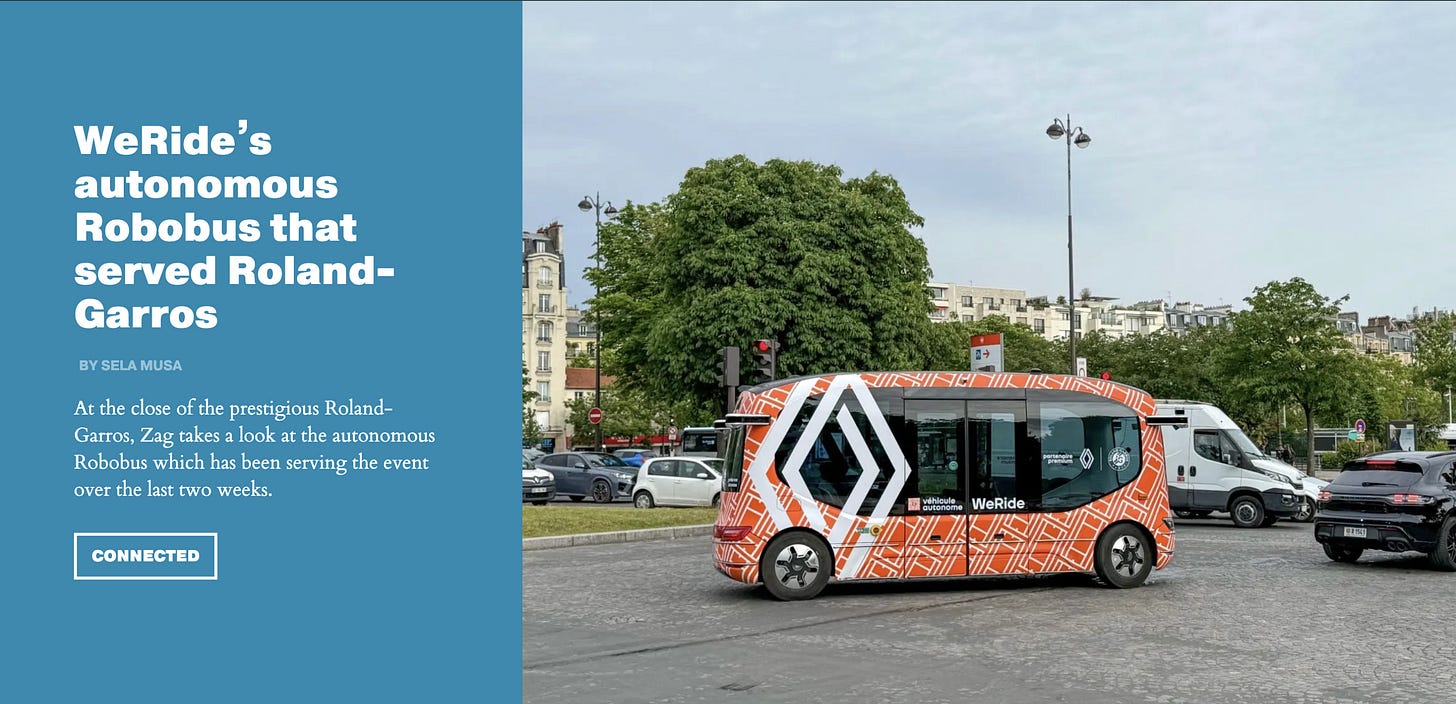

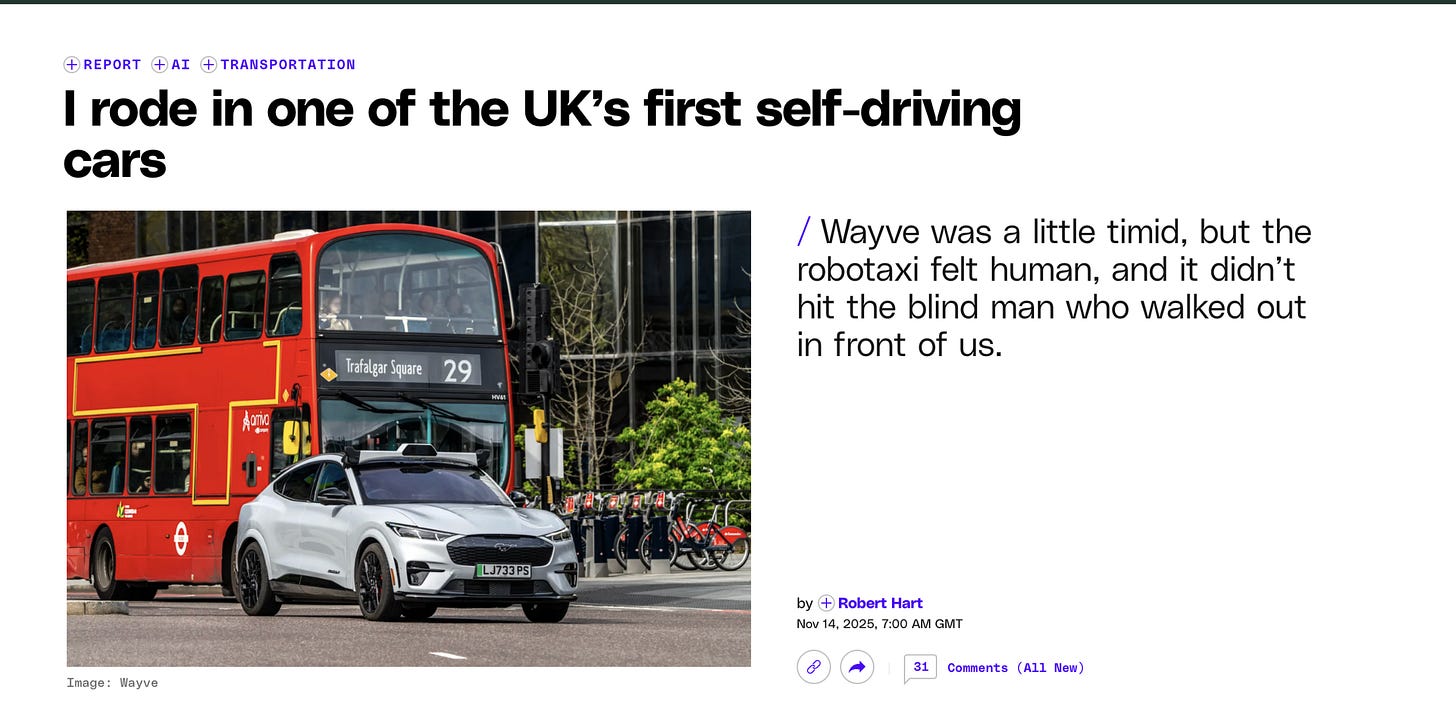

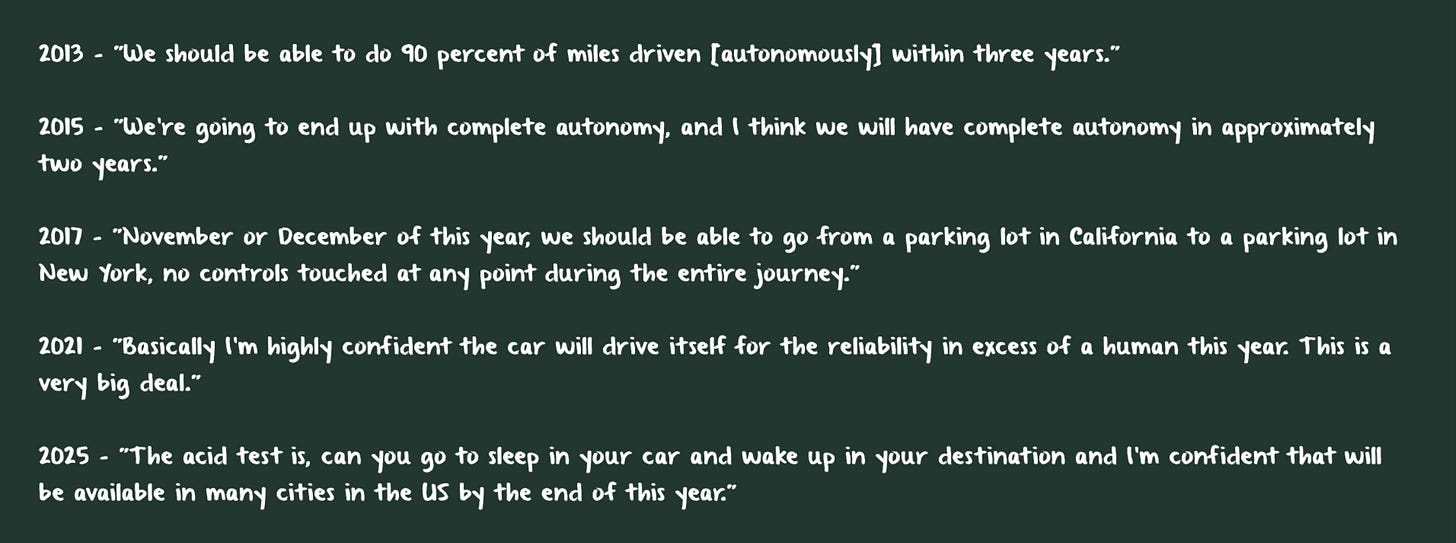

An analogous process is playing out today with autonomous vehicles. And the heroes are not CEOs who make false predictions in order to generate attention.

That said, it looks like the experience of riding in an AV will be available next year in dozens of cities, including London.

Now people were saying something like that in 2009 when breakthroughs in mapping and sensors led to a lot of excitement and investment. How long before riding in a robotaxi is as banal as a tram ride or turning on a light switch?

There is an analogous revolution happening with information. Yet again. As Ada Palmer says, “We are an information revolution species.”

Since I started working at a university, we have gone from this:

To this:

To this:

We now talk with our data using AI models built out of nearly all the machine—readable information in the world, some linear algebra, and a great deal of computation powered by electricity. Just in the last two hundred years (my list starts with the telegraph), that’s information revolution four? five? six?

The challenge with understanding this revolution is less about making effective chatbots and more about reengineering and reimagining organizational processes. This is what Paul Bascobert, president of Reuters, calls orchestration in this Decoder interview.

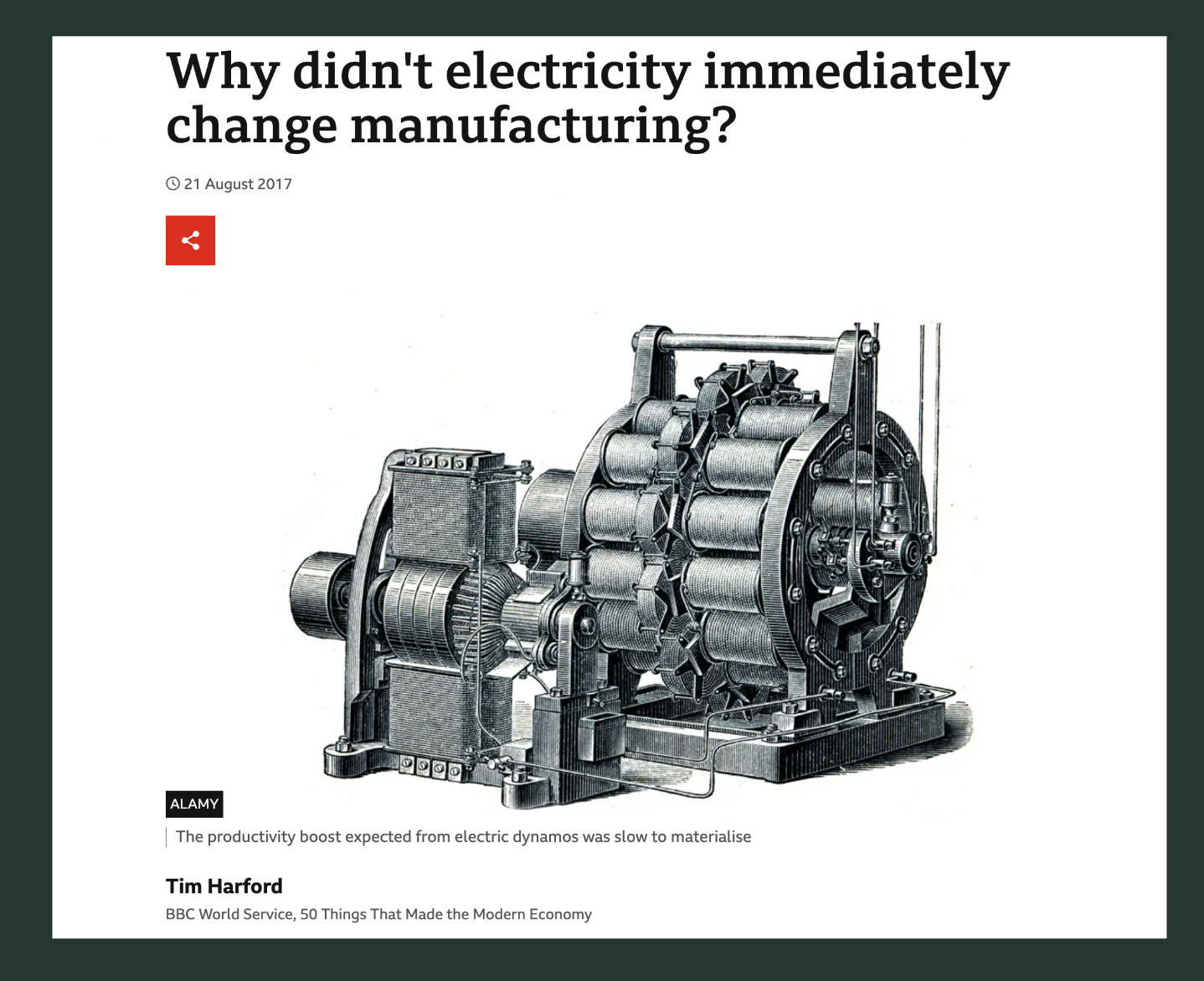

In Edinburgh, I used an analogy drawn from the history of steam and electricity to illustrate orchestration with AI. Tim Harford in this essay draws on the work of economic historian Paul A. David to make the case that just as electricity required rethinking the physical arrangements and workflow of the factory in order to realize its value.

I believe orchestrating large language models into the flow of knowledge work will be how we realize the value of large language models. This analogy does not help predict exactly how this will happen (and may be misleading!), but it does suggest the people who work in institutions of higher education will play a crucial role in how these tools are to be used. After all, universities are factories where knowledge is created and disseminated.

That puts a lot of responsibility on people who work and study in institutions of higher learning. Technology does not determine how it is used, humans do. The process takes place over decades, not months, not years, but it happens as we make decisions together. These decisions should be made thoughtfully and with the needs of humans at the front of our minds, not the needs of large corporations like universities and technology companies.

Humans are tool creators. That’s what we do. We look around our environment, and we ask: what can we create that will make our lives better? And we invent things, and then improve them and share them. And these tools, these technologies are amazing! And often, we use them too much and we use them unwisely.

In closing, I talk about the contradictions in how I am teaching a course on AI this term. In order to learn about technology, my students and I put most technology aside. I didn’t ban or prohibit digital devices, but together we decided to leave our phones on a table by the door each day, and to keep our laptops closed unless we are doing something specific for the class.

And we have done it all semester. Gladly.

I teach about twenty-first century technology in a class that uses nineteenth century educational technology, and that most ancient of all edtech, the spoken word.

I believe we should inhabit this contradiction, and follow impulses that lead us to strengthen human social connections...put our screens away, and talk about what new technology means for our selves and our society. Face-to-face conversation was the first information revolution. It defines us as a species.

Note: These are paid speaking engagements where Explorance gives me a platform to share how I believe AI is changing higher education and I help their clients and other conference attendees think about how they use generative AI in their work.

I have known the CEO and leadership team at Explorance since 2008 and trust them when it comes to the responsible development of what we called machine learning until recently.

I do not receive money or other compensation for what I publish on AI Log. When I speak or write about AI as educational technology, the views I express are my own. That includes anything I say about a commercial product or service. See my disclosures statement on my website.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

I enjoy talking with people about how AI is changing higher education and what we should do about it. Click the button below for more information.

Thanks for sharing this Rob. I find the hype about "unprecedented " pace of change hardest to get my head around. As you say, this is an important technology but it will get absorbed into how we live and work through the same mechanisms as previous waves of change. Maybe I can catch you for a coffee when you are in Edinburgh?