Language Machines as Antimeme

AI Log reviews Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism

It is very unhappy, but too late to be helped, the discovery we have made, that we exist. That discovery is called the Fall of Man. Ever afterwards, we suspect our instruments. We have learned that we do not see directly, but mediately, and that we have no means of correcting these colored and distorting lenses which we are, or of computing the amount of their errors…Nature and literature are subjective phenomena; every evil and every good thing is a shadow which we cast.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson, Experience

There is a belief devoutly held by the rationalist evangelicals working on superhuman intelligence that what they build is alien, nonhuman. Strangely, their most ardent critics believe this too. Good or evil, super or mid, whatever it is that transformer-based large language models are, both sides agree: it is not human. The difference between the prophets and skeptics of AI lies in how they enact their convictions. Rationalists fall to their knees in awe; skeptics run to the barricades.

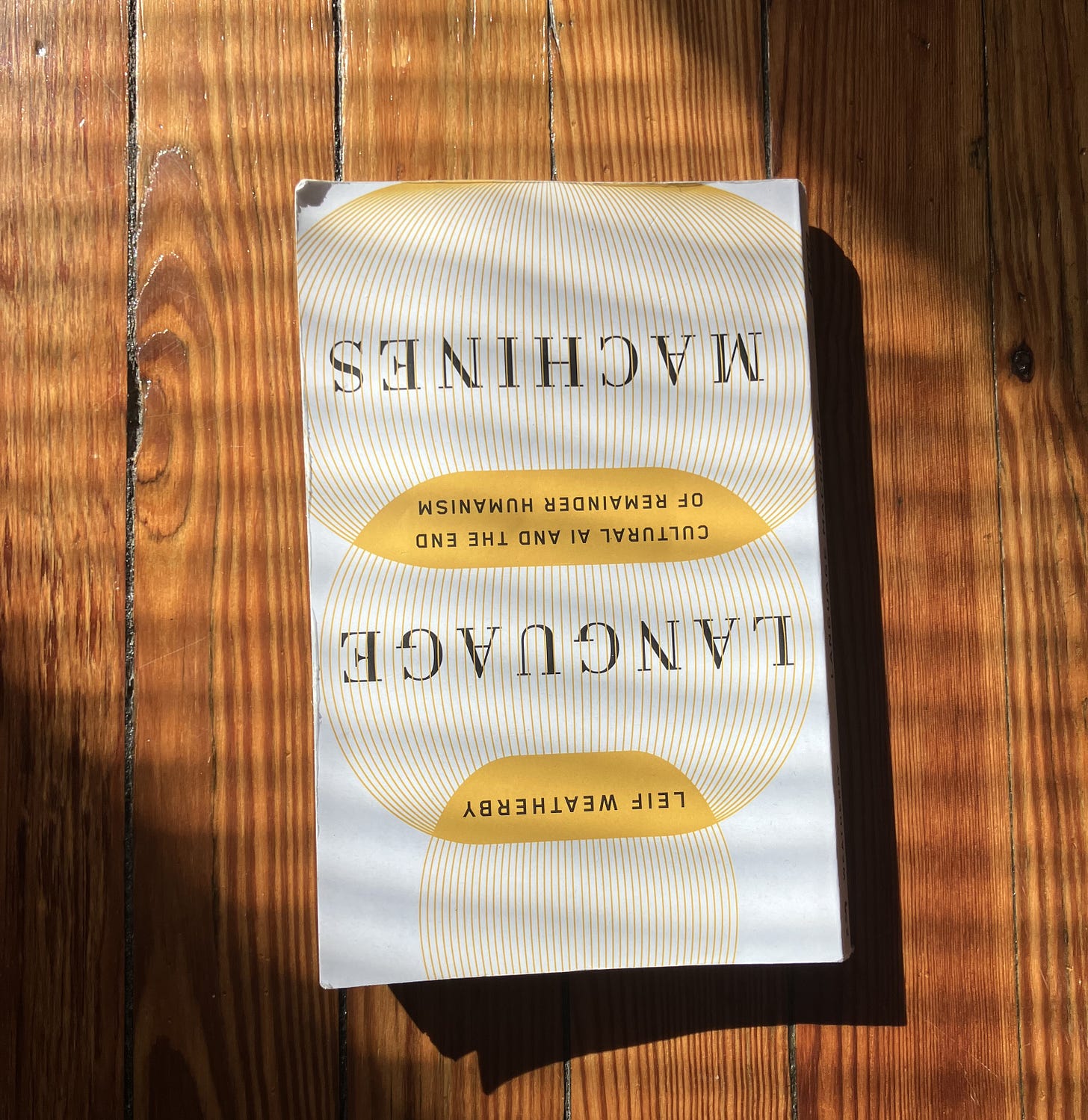

In Language Machines, Leif Weatherby uses the term remainder humanism to damn the skeptics for this shared sin. It runs them in circles, hobbled as they are by “a distorting focus” on “a moving yet allegedly bright line between human and machine.” Their blurred picture leaves them unable to think clearly about machines that produce language through computational processes. The term aims to provoke literary theorists, linguists, and scientists who study cognition and data into updating their theories.

One alternative to remainder humanism, at least for those who do not wish to join what Dave Karpf calls “not exactly a cult, but not not a cult,” is to understand transformer-based language models as cultural technology. To see these models, as Weatherby does, as “culture machines, and more narrowly, language machines.” To agree with Alison Gopnik that they are analogous to cultural tech we take for granted after centuries of use: the printing press, the graphite pencil, the open-stack library—instruments that were shaped by humans, and now shape human thinking.

It is disappointing how little attention this idea has received over the past year, despite the work of Gopnik, Henry Farrell, and their collaborators. I lump Weatherby in with those writers and the AI-as-normal-technology duo of Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, who are attempting to escape the semantic wrangling over cognition that the term artificial intelligence invites.

The medium is the massage

Kevin Munger, writing at Never Met a Science, offers a hopeful take on the prospect of moving beyond wrangling. His McLuhanesque pronouncements—“the idea of ‘antimeme’ was once an antimeme but has now, in certain spaces, become a meme” and “The antimeme is the message of the medium, defined negatively”— suggest that if we can “identify what the medium is telling us by observing what it is unable to tell us,” we might bring the actual processes of large language models into focus. Not just the algorithmic processes that produce the words, but also the social processes that make those words meaningful. He says, “Processes are the antimeme haunting Western philosophy.” A revival of cybernetics is Munger’s main interest, but he usefully widens the frame to include a genealogy of process philosophy.1

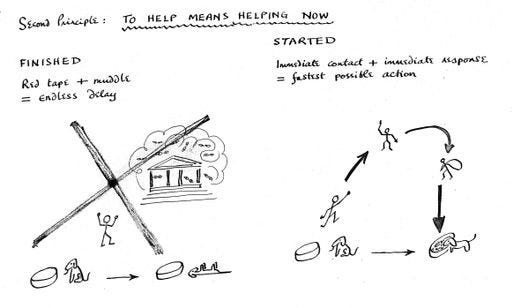

Until Dan Davies gets interviewed by Ezra Klein and Tyler Cowen, and cybernetics becomes the new hotness, I fear we are stuck with warmed-over sci-fi tropes as the framework for debating what we should do about large language models. This frame lets the participants imagine themselves in a high-stakes battle, understood by one side as heroic defenders of humanity vs. diabolical agents of the machine, and by the other as heroic makers of the future vs. diabolical Luddites standing in the doorway to paradise. We would do better with more comedy of the sort offered by Davies in The Unaccountability Machine and Stafford Beer with his back-of-napkin illustrations.

Thinking about LLMs means attending to their social and computational processes, not telling romantic tales or tragic stories. All the arguing over benchmarks and bubbles, and the prospect of the always-almost arrival of AGI, has led to a notable lack of curiosity about what generative, pre-trained transformers actually do with words. Engineers talk compute and parameters. The social critics talk next-token prediction machines and text-extruding stochastic parrots. But there is more going on than just “mathy maths.” There is a there there.2

On beyond the dangers of stochastic parrots

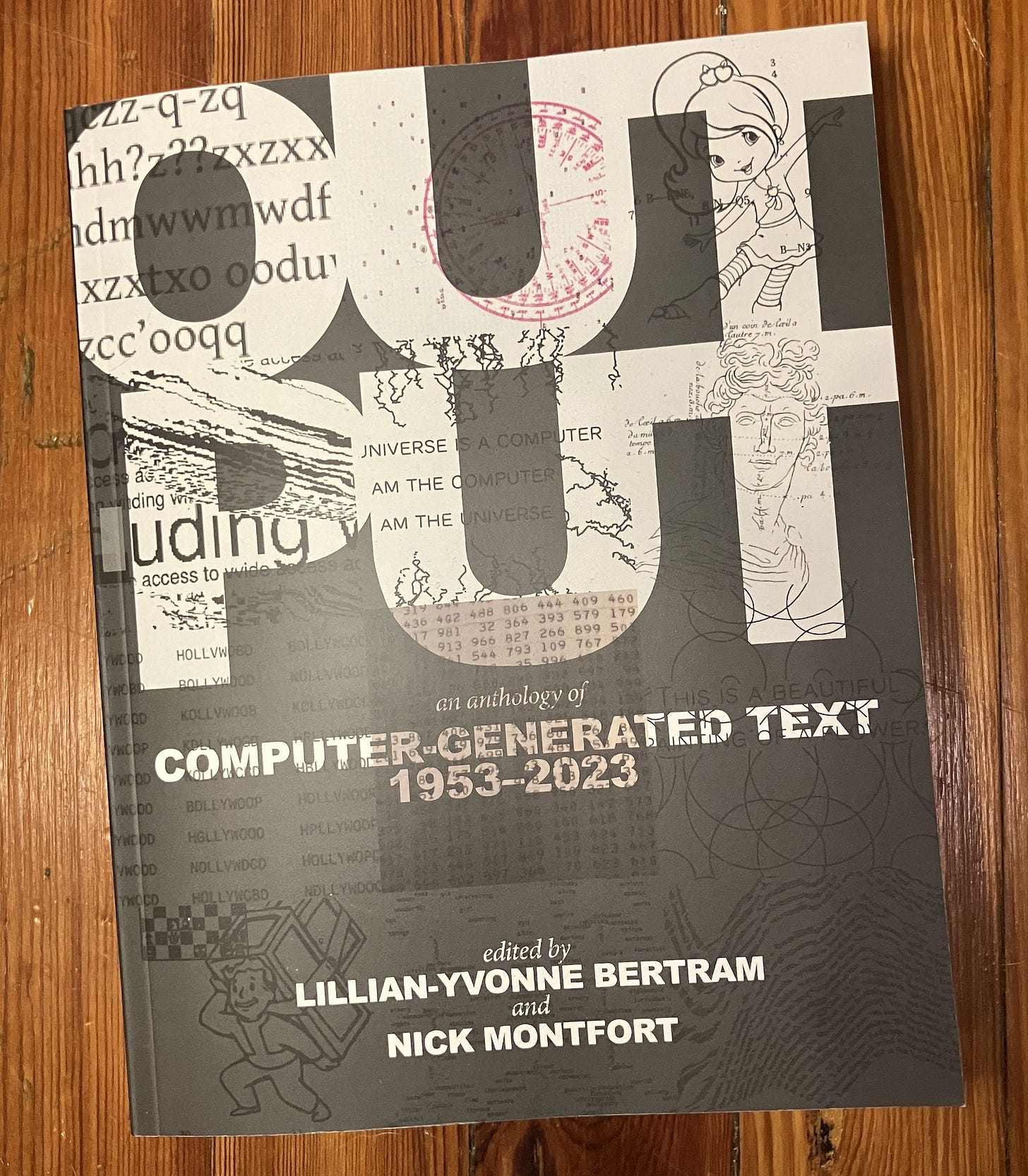

Around the same time “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots” was published, poet Allison Parrish offered another way to think about the growing capabilities of language models, arguing that “the only thing computers can write is poetry.” Instead of insisting that words generated without human intention are without context or that the human brain is the sole source of language’s meaning, Parrish distinguishes between output as form and output as art: “The poem unites poetry with an intention. So yes, a language model can indeed (and can only) write poetry, but only a person can write a poem.”3

Parrish’s notion provides Weatherby with a start toward a better theory for what he calls “language in the age of its algorithmic reproducibility,” a theory that understands LLMs as “large literary machines.” This conception grapples with what he calls “a general poetics of computational-cultural forms.” Such forms exist not only in literature, but also music and the visual arts. This argues for better theory, and for greater consideration of musicians, visual artists, and poets who work with computational machinery. After all, humans have been using stochastic machines to create culture far longer than there have been technologies called artificial intelligence.4

This history is not directly relevant to Weatherby’s project, which is committed to the history of ideas rather than the history of cultural production itself. However, both theory and history provide frameworks for thinking beyond the dualism of human vs. machine, and for thinking about computational machinery that produces culture.

Language Machines is a marvelous exploration of social theory as it relates to LLMs, at least for those comfortable with the specialized philosophical language used to talk across disciplines. For this audience, Weatherby covers a wide range of debates and ideas, arguing that the structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure and Roman Jakobson offers a promising theoretical lens for examining the complex interactions between language and computation within transformer-based language models, and visible in their outputs.

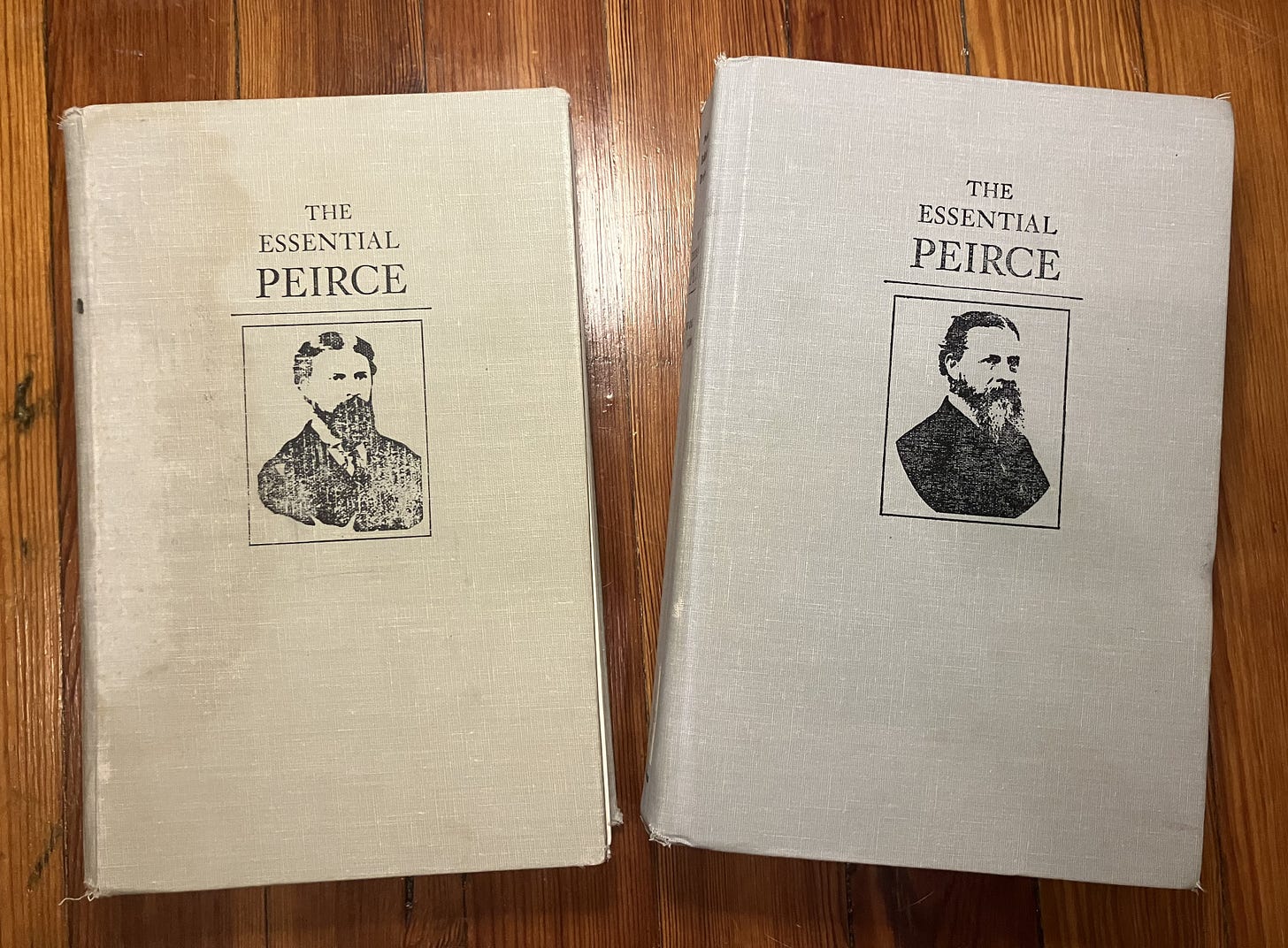

The essential Peirce

The book’s great value, even for those not so interested in structuralism, is its wide-ranging discussions—perhaps too wide for readers who prefer less winding paths—of relevant developments in social theory. The big thrill for me was discovering how many theorists are using Charles Peirce’s semeiotic these days. I frequently see references to his neologisms, like token and abduction, and assumed they were merely confirmations of my long-standing bias that Peirce, who died in 1914, is essential to understanding communication and media in the twenty-first century. Language Machines convinces me that something may be happening with this notoriously difficult thinker.5

Like his buddy William James, Peirce wrote against the dualisms that make up metaphysics as practiced by Europeans since Plato. Where James tends to mediate the two sides of any divide in search of new formulations, like his radical empiricism, Peirce names a third concept to disrupt the easy divisions of word/type, deduction/induction, or sign/signifier. This last dualism is at the center of Peirce’s semeiotic, or general theory of signs. Peirce’s third term, in this case, is interpretant, which names the process of making meaning from a sign.

Weatherby explains the process, starting with the importance of transmission in Peirce’s account of how a sign functions. “For Peirce, an untransmitted sign is no sign at all…the sign gives rise to another sign, and that second sign is called the ‘interpretant.’ This second sign is not a ‘user’ or maker of the second sign, not a mind or a person.”

Paul Kockelman’s Last Words: Language Models and the AI Apocalypse does a magnificently concise job of applying Peirce’s ideas to the problems and predicaments of LLMs. He writes, “In one sense, interpretation is simply the act or process of producing an interpretant.” The utility of this concept when applied to language produced by machines is that interpretation is no longer hidden by the blurry line separating humans and machines. Meaning happens to a sign—computationally in the case of LLMs; cognitively in the case of humans—though we need not get hung up on the distinctions.6

The breakthrough in 2022 was that we can no longer distinguish between the outputs of LLMs and those of humans, which renders the Turing Test useless. Now, we must answer questions about how machines manipulate language to create meaning, not await the arrival of thinking machines. Peirce gives us a handle. Both human and machine processes produce an interpretant. Again, Kockelman:

In other words, while machinic agents and human agents take very different paths, as it were, they can now arrive at similar destinations. At least insofar as the parameters of the former are aligned with the values of the latter, if only as channeled and distorted by the power plays of corporate agents.

Language as a service

Including Silicon Valley’s overwhelming influence in this account is critical. AI discourse is quite taken by ChatGPT and its competitors. The language of the largest AI models is channeled and distorted by their owners and their corporate agents, so when skeptics speak of AI, they speak the same language of apocalypse and optimization. But the largest models are not the only models, and chat is not the only way to use these tools.

Making other choices, in fact, just seeing that there are other choices, undermines the influence of corporate agents and tech oligarchs. Use small, open models. Boycott models made by OpenAI. Use language models to explore what Eryk Salvaggio calls “the gaps between datasets and the world they claim to represent.” Use culture machines to make art that illuminates how, as Celine Nguyen describes it, “the flaws of the medium become its signature.”

Of course, we should also pay attention to what the largest tech companies are doing as they desperately try to profit from these new toys and tools. Following Nick Srnicek, author of Platform Capitalism, Weatherby describes LLMs as offering “language as a service,” which both critiques the “as-a-service-ification" of the economy and suggests an alternative to intelligence and cognition for what the giant technology corporations are getting up to with LLMs.

“Language as a service” is not just theory. In September, Microsoft began offering Azure AI Language, “a cloud-based service that provides Natural Language Processing” to application developers. Services include detecting specific kinds of language, such as personal and health information, or the use of a non-English language or dialect. The features are basic, ranging from sentiment analysis and summarization to redacting health information and Social Security numbers. But in shifting from the brand Azure Cognitive Services to newly named services like AI Search, AI Language, and AI Foundry, Microsoft is providing a map to its offramp from the superintelligence highway to the mundane world of AI as normal cultural technology, a future in which language machines automate cultural labor just as machines powered by steam and electricity automated factory labor.

I will have more to say about “language as a service” in an upcoming essay.

In this context, Weatherby's narrative aligns with the broader neo-Luddite and remainder-humanist critique, explaining how, through the creation of new jobs from the destruction of old ones, labor becomes a matter of attending to the machines. For example, human computers were replaced by machine computers, and new occupations, like programmer and tech support, were created. Whether you call this deskilling or reskilling, the creative destruction of employment has continued into the digital age, as bookkeeping has been subsumed into the work of business analysts. As language as a service grows, the work of coding, front-line customer service, and marketing becomes ensuring the quality of machine outputs and intervening when necessary. Task automation continues the story of the digital transformation. Managers armed with spreadsheets implement new enterprise platforms and software-as-a-service solutions, making their job of counting, optimizing, and forecasting easier. This increases profits while immiserating workers and customers.

Silicon Valley desperately needs these new language machines to be a genuine wave of optimization and automation, this time aimed at language workers at the bottom of the org chart. Perhaps it will work out as they hope, but this off-modern technology may not meet the high expectations of corporate managers. Large language models, like digital computers and printing presses, serve many social functions; some of them may work against the aspirations of the owners and managers of corporations. History offers plenty of evidence that language technologies are as double-edged as any sword.

New houses, new shoes, new language

The inventors of the transformer and the engineers building with it emphasize computation when they talk about LLMs, but the functions of natural language deserve as much attention. Artificial intelligence is a problematic name, as it creates mystifications that serve Silicon Valley’s pernicious influence over how social technology is made and made available. It masks the truth that all we call artificial is, in fact, a product of human thought and natural materials. As Emerson says, “Nature who made the mason, made the house.” This applies to technologies as old and familiar as shelter, and to those as new and complex as the transformer. It most certainly applies to language, that early and most human of all cultural technologies.

Critics who insist the language of language machine is nonhuman are like architects who start from a belief that they build “artificial caves” or podiatrists whose theory for treating foot pain is that their patients wear “artificial feet.” Houses and shoes are no more alien to human bodies than are the outputs of language machines to human minds. Poetry makes use of words as both subjective stream and external object, but academic social theory often seems overmatched by the complexity of language in process. For Emerson, Peirce, and James, and the modernist poets and cultural critics they influenced, the study of literature and the study of nature are inseparable.

The disciplinary bright lines that separate these activities explain something about the absent presence of cybernetics in the discourse about LLMs. Language Machines offers antimemetic insights in its discussion of Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts, and its argument that Jakobson engaged directly with cybernetics. The connections between cybernetics and structuralism are all interesting, though I see no reason to limit the field to the structuralists. There were a lot of weird and interesting action happening under the banner of cybernetics during in the middle of the last century. For example, see Andrew Pickering’s The Cybernetic Brain and Ben Breen’s Tripping on Utopia.

Weatherby concludes the book by reading a passage from Roland Barthes’s 1964 essay “The Old Rhetoric: An Aide-mémoire,” that describes “a cybernetic, digital program” rooted in the dialectic as practiced by the Sophists. I confess, I don’t quite understand what Weatherby means when, following Barthes, he urges “the opening of this dialectic-cybernetic paradigm to probabilistic interpretation.” My confusion may be simple resistance to what I see as structuralism’s over-investment in dualisms, or it may be the first step in understanding what’s next for cybernetic cultural theory. Perhaps, it’s both.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

Note: For a review of Language Machines by a leading theorist of the cybernetic revival, see Henry Farrell’s Cultural theory was right about the death of the author. It was just a few decades early. For a concise argument that AI is human technology, see Alison Gopnik’s Stone Soup AI. For an illuminating interview with Leif Weatherby, see this post from the Journal of the History of Ideas blog.

Munger’s question is “why nobody writes about cybernetics, why there are millions of Substack posts about AI compared to just a handful by people like me, Maxim Raginsky, Ben Recht, Dan Davies and Henry Farrell.”

One answer is that if you’re interested in process, you’re probably going to build something, not write about the process of building something. I suspect those most likely to embrace cybernetic thinking are already process philosophers, they just do without the philosophy.

Another answer, more cryptic but relevant to recent cultural currents, is to say “Green Acres, Beverly Hillbillies, and Hooterville Junction.”

Seeing what’s there starts with recognizing that applying massive computation to the vast cultural datasets available on the internet produces something worth studying. To borrow a line from Cosma Shalizi, we need theories that move us, from “It’s Just Kernel Smoothing” to “You Can Do That with Just Kernel Smoothing!?!”

Parrish based the essay on a talk delivered as the Vector Institute ARTificial Intelligence Distinguished Lecture in August 2020. She extended some of these ideas last year in “Language models can only write ransom notes,” in which she argues that LLM outputs are a form of collage, that is, they are “de-authorized” text.

Brian Eno is a widely-known example, and his fame may be reason to hope that something like cybernetic cultural theory will catch on. He has had little to say about the latest language models, but here is his response to Evgeny Morozov in Boston Review and his recent interview with Ezra Klein.

As the references in this essay suggest, Eryk Salvaggio, writing in Cybernetic Forests, is the best example I can think of writing about this from the perspective of the visual arts. I adore Celine Nguyen’s essays in personal canon for many reasons, including that she engages with computation and culture.

On the pleasures and dangers of moving back and forth across the bright lines of mathematics and cultural studies, seeThe Universal and the Vacuous Events by the incomparable Rafe Meager, especially the essays Tormented by an Urn and Taking our Chances.

Please point to other writing that uses cybernetic ideas to make sense of culture produced using LLMs.

My frame of reference for social theory was formed in the 1990s as I read Richard Bernstein, Stanley Cavell, Richard Rorty, and others who attempted to mediate the analytic/continental divide in philosophy through the ideas of Emerson, William James, and John Dewey. Peirce got short shrift during this “revival of pragmatism,” largely, I think, because Rorty, its leading light, dismissed his role in originating pragmatism. Rorty’s student, Cornel West, gives Peirce his due in The American Evasion of Philosophy (1989), and Louis Menand corrected the record for a general audience in The Metaphysical Club (2001).

One problem is that Peirce’s writing is just so daunting compared to James’s affable and lucid prose. Richard Poirier, the great cultural critic and author of Poetry and Pragmatism (1992), abandoned an essay he started on Peirce forThe New Republic, writing to its editor, Leon Wieseltier in 1993, “There are for me as yet unmanageable complications in his thinking, and, especially, his writing, so for the time being I’ll have to be content with nibbling on the edges while writing more directly about others.”

Another problem is that Peirce’s ideas changed considerably over the course of his life. There is a long and distinguished list of twentieth-century philosophers writing with admiration about Peirce without generating wider interest in his work, but they don’t always seem to be talking about the same guy. Jacques Derrida, in Of Grammatology (1974), and Umberto Eco, in A Theory of Semeiotics (1976), draw on Peirce’s early ideas about semiotics, perhaps without knowing about the later iterations. See T. L. Short’s brief essay “The Development of Peirce’s Theory of Signs” in The Cambridge Companion to Peirce on this problem.

Finally, Peirce was the sole racist among the major nineteenth-century pragmatists and treated Zina Fay, the brilliant writer and activist he married, quite badly. Even if these facts did not put off potential biographers, the Harvard Philosophy department’s refusal to let anyone other than Max Fisch near their Peirce archive made writing about Peirce’s life by anyone else impossible. Fisch never completed his biography, and it is something of a miracle that Charles Sanders Pierce: A Life (1993) by Joseph Brent made it into print. It remains the only academic biography of Peirce.

We can, though! Weatherby accuses Gopnik and her coauthors of invoking a binary between cognition and culture, a charge I’m not sure sticks. This feels more like cross-disciplinary sniping than a theoretical objection. Gopnik may not delve deeply into cultural history or theory, but I hear her distinction between human and machine learning as similar to Parrish’s distinction between poetry and a poem. Both invite us to think carefully about culture and cognition as a relation occurring in language rather than as a reason to police their boundaries.

This is really excellent

This article comes at the perfect time, realy. It builds so well on your previous work on AI ethics. Your concept of remainder humanism is a brilliant way to cut through the noise in the human-machine debate. So insightful!