On Beyond AGI!

New language for talking about large AI models

Time for a new alphabet

LLM. GPT. RAG. NLP. The letters A, G, and I were a big part of what Max Read, writing a month ago, called the A.I. backlash backlash. A few pros at the NYT started talking about AGI as if it were a real thing, forcing skeptics into either ignoring what they said or pointing out the problems with the term artificial general intelligence. Most chose #2. This was what Read called a “new development in endless and accursed Online A.I. Discourse,” cycles of hype and backlash, and then hype of the backlash and backlash to the backlash.

This all seems pointless, given that we already have a precise, measurable definition of AGI. I wish writers would respect the work of the scientists and engineers lawyers and accountants who developed it. In December, The Information reported that Microsoft and OpenAI secretly agreed that AGI means an AI system that can generate $100 billion in profits. That should clear up any confusion about what we are talking about when we talk about AGI.

Last week, thanks to ChatGPT-4o’s improved image generation, the discourse moved on to a real thing that real people were doing with actual AI: converting photos to anime images and posting them all over social media. OpenAI pointed to impressive user growth, if not revenue projections, to chart its path to profitability. Skeptics had something specific to be skeptical about as users entered “Studio Ghibli” in their prompts, reminding everyone about big unresolved questions about copyright. Even better, skeptics could quote (and did!) the Studio’s auteur Hayao Miyazaki’s response when he was shown AI-generated animation: “an insult to life itself.” If you watched the entire clip from 2016, you could hear him say, “I feel like we are nearing the end of the times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.”

The distance between people doing stuff on the internet that raises copyright questions and worry that we are nearing the end times nicely sums up the AI discourse of the past twenty years. But the activity itself, as opposed to the discourse about it, illustrates something important: these machines are a cultural technology. The spike in OpenAI’s user numbers was not due to signs of emerging general intelligence or a breakthrough in getting AI models to do something of measurable economic value. OpenAI’s new users were simply having fun with a new toy.

Cultural and social technologies

All this activity supports an argument Alison Gopnik has been making since 2022: “These AI systems are what we might call cultural technologies, like writing, print, libraries, internet search engines, or even language itself.” This argument has been bouncing around academic AI discourse ever since, but this month, it seems to be snowballing its way into a genuine intellectual movement. Gopnik joined three other scholars in issuing a manifesto: Large AI models are cultural and social technologies, published on March 13 in Science.

The essay, co-authored by Gopnik, Henry Farrell, James Evans, and Cosma Shalizi, argues that we misunderstand the nature of large AI models when we talk about them in terms of general intelligence. Machines that generate poetry, pictures, homework, songs, emails, and glitchy videos are not simulating human thinking. They are functioning as a culture factory, churning out synthetic artifacts by throwing probabilistic mathematics at giant sets of digital cultural data. The outputs are surprising and weird, and may have some economic value. But like your local library’s card catalog circa 1985, what the technology does is collect and present information about human language and culture. It can describe, summarize, and categorize that culture if you ask it to, and it can generate aggressively median versions of it. The key difference is the internet is an astronomically larger data set than your library, and the tools are all digital.

The people who designed and built the first attempts at “artificial intelligence” hit on a great term for attracting research funding and the attention of journalists. But this framing around intelligence masked how much of what they were doing relied on converting culture into machine-readable form so their technology could do interesting or useful stuff with it. Eventually, and mostly by accident, we ended up building a giant, ever-updating, networked digital repository for cultural data. The network has filaments and tentacles reaching into our workplaces, homes, and pockets.

The recent breakthrough of hooking up a chat interface to “generative, pre-trained transformers” was just one more development in the giant social experiment we call the internet. Think about what people actually do with ChatGPT: they chat, make pictures, and have it to do busy work related to words and numbers. It is a cultural tool.

The academics who have taken up this framework each have their own view on how large AI models function, or could function, in social and organizational contexts, but they share a skepticism of general intelligence as a useful frame. Henry Farrell is the nexus of this project. He says, “It weaves these various strands of thought together into a broader argument that large models are not agentic super-intelligence in the making, but a new and powerful cultural and social technology.” This frame moves us beyond straight skepticism about AGI to explain the social and cultural effects this technology is having today. And, it could blunt some of the force OpenAI and the tech oligarchs are bringing to bear on getting institutions to accept these tools as replacements for human thinking.

Whether you use the $100 billion dollar definition or the squishier one, “a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work,” thinking of ChatGPT as a cultural and social tool rather than as baby AGI aligns Farrell’s merry band with what Daron Acemoglu calls an “anti-AGI, pro-human agenda.” It is a way of thinking beyond AGI to consider how AI tools might further human welfare, not simply optimize the workforce.

Big stories and big systems

Describing large AI models as something like human or superhuman intelligence has always been about selling AGI as a management tool. “The future is a marketing tool,” science fiction writer Charlie Stross explained early on in the most recent AI hype cycle. OpenAI has been particularly effective at turning stories about a future with intelligent, autonomous agents into attention and money. Dave Karpf makes the connection clear. We have “two narrative genres: science fiction and venture capital investing,” both of which require constructing interesting and vaguely plausible futures in order to attract an audience. Stories about interesting and vaguely plausible futures are a perfectly fine strategy for genre writers and VCs, but as Karpf says, “This is how science fiction works, and how VC investing works, but it is not how science works.”

Science fiction writers and Silicon Valley marketers face similar challenges with actual science not aligning with the reality they wish to create. The role of Stross and other sci-fi storytellers, like Ted Chiang especially, in deconstructing the AI discourse illustrates Karpf’s point. If you write commercially successful science fiction, you understand how the future works as a marketing tool. This gives sci-fi writers a window into Silicon Valley’s efforts to sell a good story.1

Ted Chiang was early to this sort of insight, asking questions in the early days of OpenAI.

As it is currently deployed, A.I. often amounts to an effort to analyze a task that human beings perform and figure out a way to replace the human being. Coincidentally, this is exactly the type of problem that management wants solved. As a result, A.I. assists capital at the expense of labor. There isn’t really anything like a labor-consulting firm that furthers the interests of workers. Is it possible for A.I. to take on that role? Can A.I. do anything to assist workers instead of management?

Thinking of large AI models as a social and cultural technology offers an alternative to Silicon Valley’s vision for using AI to wring more efficiency and profit out of human labor. If large AI models are social and cultural tools, they can be used for social purposes beyond replacing workers. In fact, they could be used to reconstruct corporations to achieve something more than maximizing profits.

To get a glimpse of what that might look like, read The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions - and How The World Lost its Mind by Dan Davies. I reviewed it earlier this year along with Josh Eyler’s Failing our Future because I think Davies offers a promising way to tackle the organizational problems Eyler wants to solve. The short version is that bureaucracies have become unmanageably big, and the human capacity for managing them well, or at all, has not kept up. Davies offers Stafford Beer's writing about cybernetics as a way to approach these sorts of big systems problems, a bag of mathematical models and metaphors that humans can use to understand and constrain big systems and, perhaps, change them for the better.

If we think of large AI models as a new set of tools for that purpose rather than as tools for corporate managers to optimize operations and eliminate jobs, then this historical moment is alive with possibilities. As dark as it seems, the current destruction of higher education now underway could give us the chance to rebuild universities and other institutions so they better serve the humans who learn and work there.

Mobilizing for that effort means thinking beyond AGI. It means asking how large AI models can be used as social, cultural, and educational tools to solve human problems. The Unaccountability Machine is now available in the US. The essay in Science is generating interest among academics and journalists. Reading both will give you insight into a much-needed alternative to tired back and forth about A, G, and I.

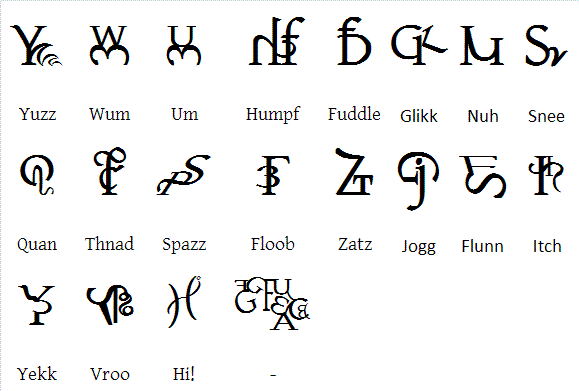

Note: The header image of the imaginary alphabet from On Beyond Zebra! was created by Snapdragongirl. The font used is Constructium. CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed via Wikipedia.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

The full story of the relations among scientists and engineers, the creators of science fiction, and Silicon Valley investors and developers is long and deep. Brian Merchant described it a few years ago in this essay: “For the past century, this messy, looping process — in which science fiction writers imagine the fabric of various futures, then the generation reared on those visions sets about bringing them into being — has yielded some of our most enduring technologies and products.”

Shall we start saying AGI stands for Alison Gopnik Inquiry?

Your inquiry is really heading in a productive direction. Thanks for these quote rich posts.