On Beyond AGI: A reading list of sorts

Read / Watch / Listen to fourteen writers on the social uses of large AI models

As Silicon Valley oligarchs continue to demonstrate how impoverished their understanding of human social needs is, I have been searching for better frameworks than AGI for talking about what social and educational value large AI models might offer.

My thanks to John Naughton for sharing my recent essay “Old ways of thinking about new problems” in his Observer column last week and on his blog, Memex 1.1, and to Josh Brake for doing the same on The Absent-Minded Professor.

The question

The brief essays below answer a simple question readers have asked as I continued to write on the themes of On Beyond AGI!: What are some essays, podcasts, or videos that will help me understand the ideas you have been going on about lately?

First, the ideas. I see three overlapping frames taking shape for thinking beyond AI as general intelligence.

They are large AI models as

a technology to be used in the revival of management cybernetics.

My hope is that the more we talk about AI in these terms, the more we will find ways to use generative AI for the public good.

The list below is incomplete and idiosyncratic. Please use the comments to suggest additions and point out where I am wrong.

Alison Gopnik

Alison Gopnik introduced the idea of generative AI as a cultural technology, “a tool that allows individuals to take advantage of collective knowledge, skills, and information accumulated through human history.” Here is a paper from October 2023 with co-authors Eunice Yiu and Eliza Kosoy. Here is a parable she published last summer about generative AI as a form of collective human intelligence.

Cosma Shalizi and Henry Farrell use Gopnikism to describe this set of ideas, but I am skeptical that we should saddle these ideas with an ism just yet. If we do, I’m not so sure an eponym is the right approach. Also, Gopnik has an unfortunate meaning in Russian slang.

Whatever the prospect for naming it, there is no doubt that Gopnik was the first to articulate the concept and introduce it into the academic discourse. For that, she deserves recognition and celebration.

Here she is on video in July 2022 describing her thinking, which also appeared that month in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal.

Henry Farrell

Farrell is the self-described “amateur facilitator” of the group of academics who are exploring large AI models as “analogous to such past technologies as writing, print, markets, bureaucracies, and representative democracies.” His blog, Programmable Mutter, is where I first saw Gopnik’s ideas about cultural production explored in relation to others on this list. Farrell may be merely facilitating these connections, but to my mind, he deserves enormous credit for that work and his own contributions to the ideas.

Farrell’s sense of the project seemed to come into focus in January of 2024, with two essays:

The political economy of Blurry JPEGs takes on Ted Chiang’s metaphor by suggesting there may be social value in “an imperfect mapping of vast mountains of textual information which interpolates best statistical guesses to fill in the details that are missing.”

ChatGPT is an engine of cultural transmission provides an overview of Gopnick’s ideas linked with those of James Evans and Cosma Shalizi, and so might be considered as originating the project that resulted in the March manifesto.

Among the many interesting ideas Farrell discusses in the back pages of Programmable Mutter is the importance of narrative fiction, especially work by Jorge Luis Borges, Philip K. Dick, and Kim Stanley Robinson, for thinking about the current moment. Given science fiction’s role in getting us into the deep hole we’re in (see Stross, Charlie), it seems reasonable to expect writers of speculative fiction to contribute to getting us out. My nominations are Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota series and Martha Wells's The Murderbot Diaries, but I’d be delighted to hear other recommendations in the comments.

For those who like to watch, here is Farrell talking about the cultural framework for AI on May 2, 2024.

Arvin Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor

Despite the sense you may get reading mainstream news coverage of AI, not every computer scientist with a public profile prognosticates. While journalists print whatever certain Nobel prize-winners say about AI as if it were validated truth, Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor make uncertainty about AI central to their project.1 Talking about uncertainty frustrates both enthusiasts and skeptics and makes Narayanan and Kapoor’s work invisible to journalists looking to tell simple stories about two sides of whatever question is at hand.

In their latest big paper, AI as Normal Technology, Narayanan and Kapoor distinguish between “two types of uncertainty, and the correspondingly different interpretations of probability” using concrete examples.

In early 2025, when astronomers assessed that the asteroid YR4 had about a 2% probability of impact with the earth in 2032, the probability reflected uncertainty in measurement. The actual odds of impact (absent intervention) in such scenarios are either 0% or 100%. Further measurements resolved this “epistemic” uncertainty in the case of YR4. Conversely, when an analyst predicts that the risk of nuclear war in the next decade is (say) 10%, the number largely reflects ‘stochastic’ uncertainty arising from the unknowability of how the future will unfold, and is relatively unlikely to be resolved by further observations.

So much of the anticipatory hype around AI is driven by unknowability. To illustrate how to think about stochastic uncertainty, especially speculation about how plausible it is that an artificial intelligence model will suddenly behave in ways that pose an existential risk to humanity, Naranayan and Kapoor imagine how Nick Bostrom’s AI paper-clip maximizer might develop in the real world. They point out that such instrumental convergence is unlikely to appear suddenly and without warning. Powerful AI models “would need to demonstrate reliable performance in less critical contexts“ before they are deployed.

Consider a simpler case: A robot is asked to "get paperclips from the store as quickly as possible." A system that interpreted this literally might ignore traffic laws or attempt theft. Such behavior would lead to immediate shutdown and redesign. The path to adoption inherently requires demonstrating appropriate behavior in increasingly consequential situations. This is not a lucky accident, but is a fundamental feature of how organizations adopt technology.

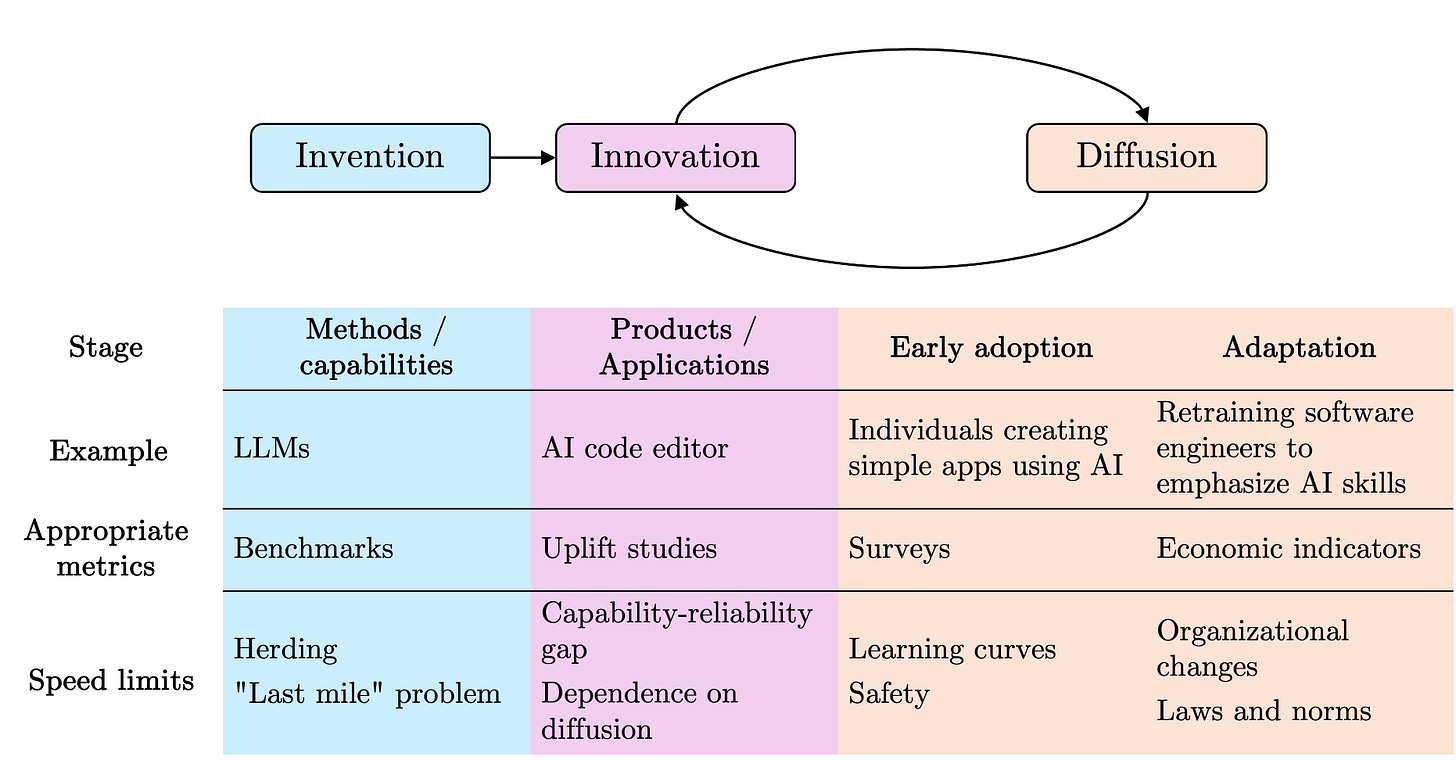

One theme that connects all three frameworks shaping this list is that we should think more about how organizations and social systems actually adopt technology. Speculative stories about how machines might one day behave are entertaining, but not instructive. Better to acknowledge unknowability and think instead about the messy social processes represented in this chart from the paper, labeled The Speed of Progress:

My shorthand for talking about diffusion is to say that the adoption and adaptation of new technology happen at the speed of humans, not machines. Early adopters (and those cynically trying to profit from them) describe how a new information technology should transform everything, everywhere, all at once. Their enthusiasm blinds them to the ways that things that feel so right in theory never work out in practice. When unknowably complex human social systems encounter new digital technology, everyone rediscovers Hofstadter’s Law: “It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law.”

The feedback loop represented by the arrows at the top of the figure connecting innovation and diffusion shows how implementing digital tools works in the world as it exists. The slow, frustrating humans who hesitate, ask questions, and come up with other ideas about what to do add time and value to the process.

If you can handle the early morning, drive-time DJ energy of Kevin Roose and Casey Newton, you should listen to this interview with Narayanan on Hard Fork.

Here is Narayanan returning to MIT, where he gave the talk “How to Recognize AI Snake Oil” in 2019 that launched AI Snake Oil, the blog and the book. He talks briefly about AI as normal technology toward the end. The conversation that starts around the 27-minute mark with Daron Acemoglu, who probably ought to be on this list, is particularly worthwhile.

Melanie Mitchell

Like Naranayan and Kapoor, Melanie Mitchell explores the social contexts of AI without prognosticating. Her Expert Voices column in Science, which started in 2023, has been a treasure of thoughtful analysis about the reception of transformer-based AI systems.

In The Metaphors of Artificial Intelligence, Mitchell discusses the importance of language in shaping our understanding in ways that avoid taking a side in the various debates.

The metaphors we humans use in framing LLMs can pivotally affect not only how we interact with these systems and how much we trust them, but also how we view them scientifically, and how we apply laws to and make policy about them.

She points out that the pervasive metaphor of AI as mind shapes AI's legal and policy contexts, including framing the ongoing lawsuits filed against AI companies over their use of copyrighted material.

A principal argument of the defendants is that AI training on copyrighted materials is “fair use,” an argument based on the idea that LLMs are like human minds.

Mitchell's two most recent books, Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Humans and Complexity: A Guided Tour, are the best accounts for general readers of two ideas entangled in all three frameworks I laid out at the beginning of this essay.

She appeared with Arvind Narayanan at an event at Princeton in March that left me wishing more journalists looking for quotable experts were talking to the two of them rather than the prognosticators.

Cosmo Shalizi

Shalizi’s writing on Three-Toed Sloth is among the most interesting experiments in writing on the internet. Reading it has added many titles to the list of books I really need to get to and many concepts to the list of things I can name but do not understand well enough to speak or write about with any confidence. Four or five times a year, I lose an afternoon to rambling through the labyrinth that is this thick web of brief essays. My time is never wasted.

Shalizi is a skeptical guide to key concepts of the recent breakthroughs in machine learning, including artificial intelligence, neural networks, and this collection of thoughts about how attention is used in the “Attention is all you need” paper. His page on collective cognition is a curated collection of readings on the topic and links to his own early (as in 2002 early) efforts to define the term.

Shalizi collaborated with Farrell in writing Behold the AI shoggoth in the summer of 2023. There is also this 2012 essay about Cognitive Democracy.

James Evans

James Evans argues for analogizing AI to alien intelligence rather than human general intelligence. I’m as skeptical of xenomorphizing large AI models as I am of the much more common practice of anthropomorphizing them, but Evans uses the idea of alien AI to think about these tools in relation to the collective intelligence of humans. This is a more interesting frame than individual minds, alien or human, and seems to have practical value in the work Evans does.

Here is the TED Talk:

Consistent with the others in the group, Evans does not see AI models as replacements for human thinking but as tools that can help us better understand and guide human thought and action. Evans describes the work he and his team do at Knowledge Lab to “reimagine deep neural networks as social networks that simulate discussions and disputes between people with diverse perspectives.” He believes we should not aim to create a single, best system but take a plural approach that creates “an ecology of diverse AIs that will balance each other.”

The largest and latest AI models get all the attention, but many specific organizational problems are better solved using smaller, open-source models trained on datasets that are not so huge and not so stolen and built to solve specific problems. Orchestration of different types of AI systems within organizations and outside them is an emerging problem that few are talking about, and that Evans seems to anticipate.

Beyond Dan Davies: Andrew Pickering and Benjamin Breen

The Unaccountability Machine argues for cybernetics as a collection of management ideas and practices that could help with our current public problems, including the orchestration of various human and AI decision-making systems. Are large AI models management tools that could help turn corporate entities into producers of positive social outcomes? Could big systems make better decisions, reducing the frustration and anger expressed in recent outcomes of elections around the world? Davies sketches a picture suggesting the answer could be “yes” to both questions.

I suspect the picture most American readers have of cybernetics is centered on the work of Norbert Wiener and Claude Shannon, a story well told by James Gleick in The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood. The Unaccountability Machine offers weirder, funnier, and possibly more useful stories about cybernetics. I hope its North American publication by the University of Chicago Press occasions a broader appreciation. You should read reviews by Brad Delong and Henry Farrell to understand why this book is important. I reviewed it here in the context of higher education.

When you finish The Unaccountability Machine and want more, I recommend The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future by Andrew Pickering. Pickering takes his readers into more philosophical waters while expanding the cast of characters, placing Stafford Beer in the context of an eclectic mix of British psychiatrists, artists, and free-thinkers. In Pickering’s story, cybernetics in the UK is an alternative to the more familiar North American version, which developed mostly within the military-industrial complex and aimed for command and control of systems. The cyberneticians in the UK had a different understanding of power and a more expansive sense of the social purposes of technology. Pickering’s new book, Acting with the World, is just out from Duke University Press and on its way to my local bookstore. Along with Danielle Allen (up next), Pickering seems to be the writer doing the most to extend the insights of philosophical pragmatism to the current moment.

For those who want to stick to the US context, Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of a Psychedelic Science by Benjamin Breen describes Mead and Gregory Bateson, a major figure in The Cybernetic Brain, as engaged in a similarly weird science. The story Breen tells ends with Bateson’s death in 1980, but it suggests that psychedelic science lives on, at least in the potential revival of inquiry into “these mysterious, fascinating, and deeply misunderstood substances.” Both Pickering and Breen offer a history of science that was not quite, but could one day be, a genuine alternative to the progressive stories we tell about institutional science uncovering reality through rational explanation of observations.

Seen through the lens of what Pickering calls a nonmodern ontology, cybernetics is a science, or perhaps just a collection of methods and practices, that treats the world as open-ended and ever-changing. This ancient idea, revived and incorporated into experimental science by William James and functionalist psychologists in the nineteenth century, is in tension with the precepts and habits of nearly all social scientific inquiry.2 As such, James, Bergson, Dewey, Bateson, Beer, and their collaborators, friends, lovers, kids, and enemies are historical sources for an alternative future reaching back to Darwin and looking forward to approaching large AI models as a weird technology with social purposes that could bend to democratic purposes.

Danielle Allen

If “representative democracies” are to be included among the analogous technologies for large AI models, then Danielle Allen’s work rethinking the institutions of democracy is quite relevant, as is the last decade of experimentation in Taiwan and the United States Digital Service before it was repurposed by the Trump regime.

You can hear Allen and her colleague Mark Fagan talk about AI's potential for democratic experimentation in this podcast from March: AI can make governing better instead of worse. Yes, you heard that right.

Allen recommends that governments experiment with AI to enhance “openness, accountability, and transparency.” She also promotes an alternative, pro-social model for social media platforms that could usefully be joined to the analysis in The Ordinal Society and AI Snake Oil. While we fight the ongoing destruction of institutions by and within the federal government, Allen reminds us to pay attention to state and local governments. Given what’s happening at the federal level, smaller-scale experiments are where we can start now with digital democracy in the US.

I include Allen because she is for us today what John Dewey was to the 1920s and 1930s: the political philosopher best able to defend and describe the value of democracy in a world facing rising fascism and authoritarianism. The fact that she is thinking seriously about the role AI might play in fostering democratic processes is a promising alternative to the tendency among smart people in the academy to treat any experimentation with large AI models as submission to the authoritarian dreams of Silicon Valley.

Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy

The Ordinal Society uses social theory to understand how and why digital data (not just digital technology) have changed society over the past fifty years. The authors explain the emergence of digital capitalism and the importance of algorithms as the consequences of human social behavior, not simply as a conspiracy shaped by the enormous concentration of financial and social capital in Silicon Valley.

Fourcade and Healy help make sense of large AI models as tools developed to put the giant digital dataset that is the internet to work producing outputs that humans desire, even as they often feel oppressed and degraded by their social effects. I have a lot more to say about this in my review essay.

Here is Healy on an episode of Sean Carroll’s Mindscape podcast, which has also featured Ben Breen, James Evans, and Alison Gopnick as recent guests.

Fourcade is the co-author with Farrell of Large language models will upend human rituals, published in the Economist last September. Here she is giving a lecture on the book.

Brad DeLong

DeLong’s writing about what he calls MAMLMs—Modern Advanced Machine-Learning Models—is in the grain of “AI as a social and cultural technology.” DeLong seems to think so, too. He promoted Farrell’s work in this area from the beginning and recently described “the enormous intellectual gravitational pull” of the project.

Delong argues we should “understand LLMs as flexible interpolative functions from prompts to continuations” and not as brains. This is compelling, even if it does not work as a slogan the way “AI is normal technology” does. Using precise language is harder than repeating the tired analogy of AI models as research assistants or weird interns, but it has the benefit of agreeing with the reality of what we know about how large AI models actually work.

The sheer volume of DeLong’s output makes it hard to find his MAMLM posts, but they contain insights, large and small. Grasping Reality, his Substack, offers a great deal more than analysis of large AI models, much of it aligned with how Davies views economics and politics and how Gopnik and Farrell see AI.

If you made it this far and are ready to read more, DeLong’s review of The Unaccountability Machine should be your next step.

Your name here?

I could do more curation, but my purpose is to sketch what seems like a promising direction of travel, not catalog every relevant thinker. I’m curious to know what you make of this list of writers. Is a Part 2 warranted? If so, who should be on it? Know someone who might have some ideas?

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

The chapters in AI Snake Oil on predictive AI and the section “Embracing Randomness” in the last chapter of the book are a thoughtful exploration of the contingency of all scientific inquiry.

Breen has a book project going, “a group biography about the transformations of science and technology in the 1880s through 1910s.” He writes, “James, more than anyone, I think, recognized both the irreducibility of even scientific knowledge to a single set of data or axioms, and also understood that consciousness is rooted not just in abstract reasoning but in a physicality, a sensation of being a person in the world.”

Thanks for this: I have a bit of form here myself, having been making films about this stuff for 30+ years: in 1992 'The Electronic Frontier' for the BBC/Nova asked 'What would the world look like with information as money?' and foresaw the computer in your pocket (13 years before the iPhone), the death of Main St, ubiquitous surveillance via smart devices and DeepFakes, including their political risks. Then 'Truth Decay' in 2020 on the death of reality, etc. So I'd like to add a couple of names to this list: Ed Zitron, always splenetic but fantastically detailed forensics of the truth behind the hype https://www.wheresyoured.at/, and Casey Mock, who has been on all sides of this fight and sees the big picture https://www.tomorrowsmess.com/. Obviously also Margaret Mitchell, Emily Bender and all the other women thrown out of tech jobs for daring to question its priorities. Many many others but this is a start, perhaps. Thanks, as ever, for these posts

This is a fascinating list Rob - thanks for sharing. I guess my instinct comes down on AI as a normal technology but I am going to some deeper reading. A few names on this list I am not familiar with. Not sure how reviving management cybernetics fits here. I think this is an interesting model but not especially linked to how AI plays out.