With a Certain Pathetic Moderation: AI as a New Social Medium

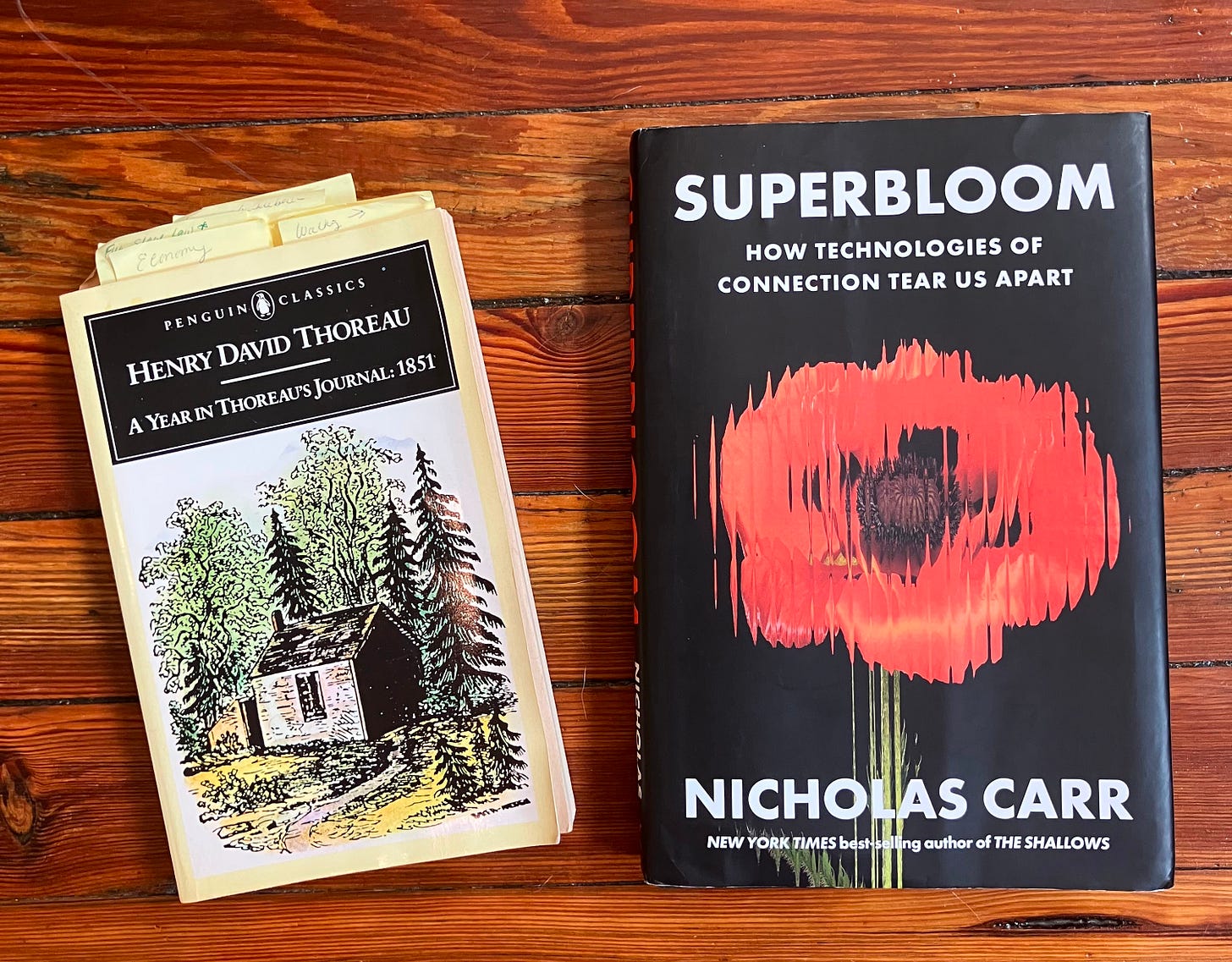

AI Log reviews Superbloom by Nicholas Carr

In addition to Superbloom and several other excellent books of technology and social criticism, Nicholas Carr writes New Cartographies on Substack.

The railway, telegraph, telephone and cheap printing press have changed all that. Rapid transportation and communication have compelled men to live as members of an extensive and mainly unseen society. The self-centered locality has been invaded and largely destroyed.

—John Dewey, “Education as Politics” in The New Republic (1922)

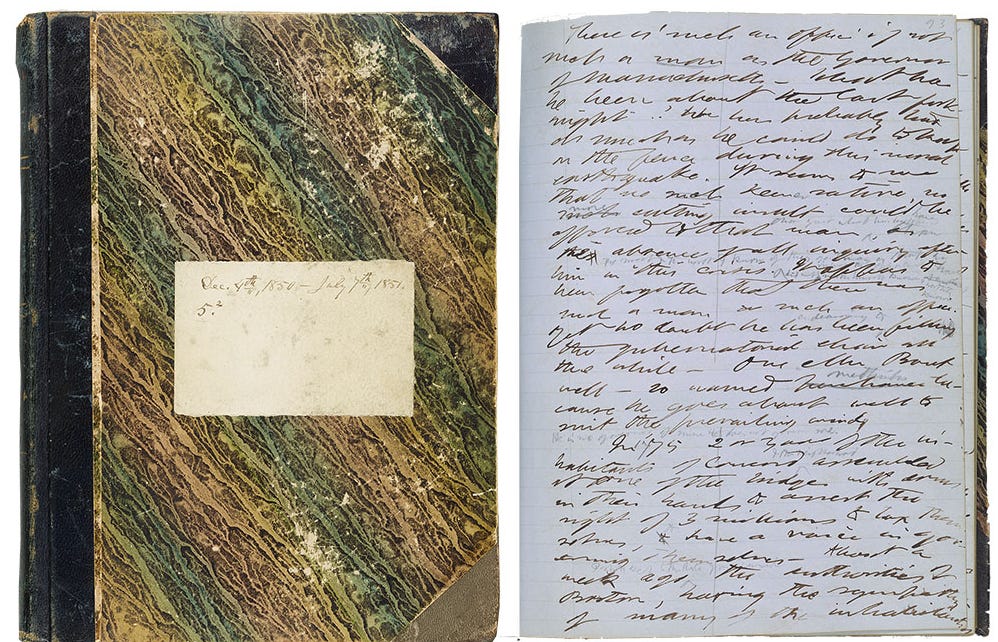

Henry David Thoreau kept a journal—he might have called it a log—from the time he graduated college in 1837 until a few months before his death in 1862. We usually think of Thoreau writing about the natural beauty he experienced at Walden Pond or while traveling on the Merrimack River. Or, picture him sitting in jail protesting slavery and an unjust war, writing sentences like “Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine.” Yet Thoreau was a keen observer of the technologies changing his world. The new modes of manufacturing, the railroad, and the telegraph were as essential to his writing project as his observations about nature and social justice.

On January 2, 1851, inspired by the new year, he began writing in a new notebook. Most of his entry on the first, fresh pages describes in detail what he saw while visiting the Gingham mills, one of the many new manufacturing facilities appearing around Boston. Thoreau could be enthusiastic about what he saw in new technology. Later that year, he wrote in his journal:

As I went under the new telegraph wire, I heard it vibrating like a harp high overhead. It was as the sound of a far-off glorious life, a supernal life, which came down to us, and vibrated the lattice-work of this life of ours.

He returned to this theme a few days later, writing that listening to the vibrations “reminded me, I say, with a certain pathetic moderation, of what finer and deeper stirrings I was susceptible, which grandly set all argument and dispute aside, a triumphant though transient exhibition of the truth.”

The next week, he abandoned any sense of moderation, to describe putting his ear to the wooden posts on which the wires were strung, and hearing music, “as if every fibre was effected and being seasoned or timed, rearranged according to a new and more harmonious law. Every swell and change or inflection of tone pervaded and seemed to proceed from the wood, the divine tree or wood, as if its very substance was transmuted.”

He concludes this passage by proposing a modern Muse to honor the invention, and proclaims the telegraph, “is this magic medium of communication for mankind!”

Superbloom does not mention Thoreau, though these reflections on the telegraph illustrate the main theme of Nicolas Carr’s new book: our longstanding cultural habit of greeting each new communication technology with enthusiasm, and then slowly realizing the problems it creates. As he puts it, we don’t see the ways that “technologies of connection tear us apart” until it is too late to do anything about them.

Superbloom explains how this cycle has played out over the past 180 years. From Thoreau’s “magic medium” to Marconi's boast that radio makes “war impossible” to technology writer Orrin Dunlap’s prediction in 1932 that television would “usher in a new era of friendly intercourse between the nations of the earth,” Carr describes how each new communication technology appears as the light at the end of the tunnel of human misunderstanding only to discover Harold Innis’s disappointing truth: ”Enormous improvements in communication have made understanding more difficult.” Carr’s point is that it is not just that our new tools fail to live up to their promises; they roll right over us, destroying social structures built with previous technology and eroding modes of communal living.

Thoreau was quick to see the dark side of the technologies of connection of his day. By the time he wrote Walden, two years after his reveries about the telegraph, he had turned skeptical. He calls the railroad and the telegraph “pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end.” Among Thoreau’s most memorable passages about technology is one about the human cost of building networks of iron rails held together by wooden ties, also known as sleepers.

We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us. Did you ever think what those sleepers are that underlie the railroad? Each one is a man, an Irishman, or a Yankee man. The rails are laid on them, and they are covered with sand, and the cars run smoothly over them. They are sound sleepers, I assure you.

For the past decade, we have been asking similar questions about the digital networks that promised so much when we first encountered them. We have come to understand that we do not communicate through the internet; the internet communicates through us. As Thoreau says, we have become the “tools of our tools,” and the internet-connected platforms that seemed to promise freedom and democracy in the early days of Google and Facebook now make us feel oppressed and trapped. Carr describes how these same companies, now joined by OpenAI and Anthropic, are building a technology that runs smoothly over our minds: “Live in a simulation long enough, and you begin to think and talk like a chatbot. Your thoughts and words become the outputs of a prediction algorithm.”

As we awaken to the social and psychological problems associated with using these newest pretty toys, the question is, what can we do to change things for the better? Can we shape the tools that now shape us? Carr believes we lost the chance: “Now, it’s too late to rethink the system. It has burrowed its way too deeply into society and the social mind.” His hope, such as it is, is not to change the system. Too late for that, he says, “But maybe it’s not too late to change ourselves.” As Carr sees it, living our lives as a counter-friction to these machines is the only remaining option.

In looking to the individual self as the means for social change, Carr is writing in the tradition of “moral perfectionism,” which philosopher Stanley Cavell understands as originating with Emerson and Thoreau, especially in Emerson’s democratic faith that each of us can shape the world through the attempt to perfect “our unattained but attainable self.” Walt Whitman is the great poet of such striving, and James Baldwin, perhaps, the great example in the twentieth century.1

Not trusting social or political movements, these writers look to the self and self-expression to reform an immoral society. They hold democracy sacred and believe that in each individual, in Whitman’s phrase, “Nestles the seed Perfection.” After all, what stops me—what stops any and all of us— from attaining a self that closes my social media accounts, shops local, votes in every local election, and uses only open-source computing products and software?2

Carr’s neglect of the writers who inaugurated the tradition in which he writes is easily forgiven because, by reminding us of Charles Horton Cooley, he does something more valuable than revisiting Thoreau, who, after all, still regularly appears in our cultural discourse as the leading techno-skeptic of American letters.3

Charles Horton Cooley, the original academic techno-optimist

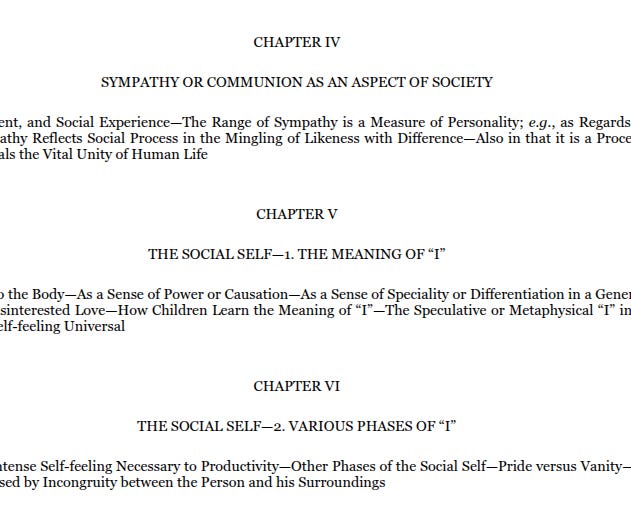

Superbloom rescues Charles Horton Cooley from obscurity. A faculty member at the University of Michigan starting in 1894 until his death in 1929, Cooley was among the generation of writers and researchers who created social science as we think of it today, organized into disciplines and housed in universities. His major works range across those disciplines, covering communication, organizational dynamics, transportation economics, and social psychology. His most influential concepts were the looking-glass self and primary groups, which described processes of identity formation just as the boundaries between psychology and sociology were being marked.

Like most of the group associated with the Chicago School (think symbolic interactions in the 1890s, not neoliberal economics in the 1950s), he kept his distance from the pseudo-scientific racism that permeated academic biological and social science in those days. One of his first academic papers was a critique of Francis Galton’s Hereditary Genius (1892). Yet, again like many of his colleagues, he never involved himself in politics and ignored the path-breaking sociological work of W.E.B. Du Bois in The Philadelphia Negro.4

As Carr demonstrates, Cooley was among the first academic theorists of communication technologies. He coined the term social media in 1897 in “The Process of Social Change,” an essay published in Political Science Quarterly. In it, Cooley sketches ideas that later academics like Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan made famous, applying the now ubiquitous term quite broadly, and understanding social media’s origins in the ancient combination of writing and maritime navigation that spread the words of the earliest social media influencers, including those we still know today: Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Socrates.5

Understanding media is, for Cooley, as for Innis and McLuhan, a matter of thinking about the processes of social and technological change across long periods of history. Just as McLuhan brought broad historical context to understand the new media of the mid-twentieth century, Cooley addresses those of the nineteenth: “the new means of communication, — fast mails, telegraphs, telephones, photography and the marvels of the daily newspaper, —all tending to hasten and diversify the flow of thought and feeling and to multiply the possibilities of social relation.” He explains the increased speed of the means of communication and the attendant processes of social change with an extended analogy.

A thick, inelastic liquid, like tar or molasses, will transmit only comparatively large waves; but in water the large waves bear upon their surface countless wavelets and ripples of all sizes and directions.

The new means of communication produce an effect that “may be described as a more perfect liquefaction of the social medium.” From the perspective of users of today’s technology, information in the past moved slowly across space and time, making change visible in the archeological record and then in written historical records. What appears today as the slow movement of information via sailing ships and the printing press accelerates rapidly, starting in the decades Thoreau wrote his journal, as new networks were built from telegraphs and steam engines. The combination of steam power and the telegraph sped information around the globe, spreading cultural, political, and scientific change.

If Cooley worried about the effects of these changes, say in the truthiness apparent in the journalism being invented by writers and editors working for Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, he does not mention it. In his blindness to what Carr calls “the more ominous implications of his argument,” Cooley is not so different from those who wrote about how digital social media would accelerate the spread of democracy or those who see the latest AI models ushering in an age where humans will have their material wants provided by machines of loving grace.

In Cooley’s time, as now, social media operates through systems managed by webs of wealth and influence that work to preserve the power of elites. Despite the persistence of anti-democratic politics in every democratic political system, there is something about the arrival of each novel means of communication that opens our minds to the hope that, as Thoreau put it, we will “grandly set all argument and dispute aside” to experience “a triumphant though transient exhibition of the truth.” Carr positions Cooley and Mark Zuckerberg as bookends of the twentieth century’s optimism about each new mechanism for communication. If the First World War and the rise of totalitarian regimes ended the hope that Cooley’s new media were the harbingers of peace, then the story of Facebook’s fall from a company commercializing a social technology that promises human connection to one that delivers a product that tears us apart brings us to the end of another cycle.

People in the early decades of the last century faced a global rise in authoritarianism and a thrilling sense of possibility about new technologies, both sped along by waves traveling through the liquefying force of new social media.

Realizations about what the commercial internet had become were just sinking in when the pandemic severely limited our means of socializing. In Carr’s telling, this was the moment when “the social and the real have parted ways. No longer tied to particular locations or times of day, social situations and social groups now exist everywhere all at once.” And, it’s true that the liquefying force of digital communication technology was intensely felt as we were confined and isolated. But, when exactly did the social and real become estranged? When Zuckerberg built a tool “to make the world more open and connected”? When radio and film gave us two new magic mediums of communication? When Thoreau heard the magical telegraph “vibrating like a harp high overhead”? When Socrates told Phaedrus that writing “will introduce forgetfulness into the soul of those who learn it”? Does it all go back to those damn kids painting in the caves?6

Social media is bad for you, always has been

In Thoreau’s Axe: Distraction and Discipline in American Culture (2023), Caleb Smith offers “a genealogy of distraction and the disciplines of attention, going back to Thoreau’s era,” putting together an impressive range of documents that explore the nineteenth-century sources of our predicament. He points to the failure of individual moral perfectionism to address the problems.

Even after we understand that distraction’s real causes are in the large-scale economic systems and technologies that shape our world, we keep trying to solve the problem with personal, moral remedies.

Like Smith, I find meaning in nineteenth-century writing as “relics of a troubled past and as crafted objects of sustaining beauty.” But the moral perfectionism of Thoreau and Carr offers little evidence that being the change you want to see in the world is a recipe for solving problems created or exacerbated by social media. Smith’s tracing of anxieties past provides context for the social scientific worries of the present, especially the writing of Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge.

Carr brings an even hand to their attention-grabbing work, pointing out narrowly focused social science methods “obfuscate as well as illuminate,” and that “sometimes you have to lift your eyes and take a wider view.” That view offers plenty of evidence that adolescents feel more depressed these days. But the reasons for this are unlikely to be singular. Why are adolescents increasingly likely to stay home and on their screens, instead of taking part in traditional activities like gathering in church on Sundays, singing together, and celebrating the harvest each fall listening to popular music together, consuming alcohol and other recreational drugs, and having sex with their friends? Pinning the problems on a particular technology ignores a complex set of correlated and confounded factors at play, and the long history of anxiety about the cultural habits of the young.

As a fan of free-range parenting who worries about constant supervision of young people, I’m partial to studies that suggest we may be seeing ill effects from keeping kids indoors, permanently cancelling recess, and eliminating old patterns of free play in the woods, in the streets, and at the malls. Social media, especially the nightly TV news and newspaper headlines, digital news feeds and Amber alerts, play a part in these changes, producing a sense that stranger danger is an ever-increasing threat and creating parenting habits that would seem bizarre to earlier generations.

Keeping kids at home and always in sight, to say nothing of turning schools into contests centered on high-stakes, standardized tests, is a recent shift in behavioral norms that helps explain why escaping into screen time is so alluring. It also frames data suggesting an increase in exercise and a reduction in alcohol use, especially among young people, in an interesting light. Maybe the kids are finding their own path back to alright?

I am convinced by Carr and others that young people are choosing to live in what he calls a “world without world.” I am not convinced that these simulated worlds are all that different from the worlds created by adolescents using earlier social media. Is crafting a self on a YouTube channel so different from writing a journal? Are the teens disappearing into their screens to play video games and watch make-up routines so different from a young person in the 1850s writing in a diary about reading a novel by a Brontë sister or a teenager in the 1980s listening to Prince on a Walkman and starting a zine?

What makes Cooley such an interesting writer for this moment is that he and his colleagues constructed a theory for understanding self-formation through social groups and shared social identities. Self-fashioning as a social experience was described by writers ancient and modern, but it was first articulated in terms of the new, post-Darwinian social science in the late nineteenth century, most notably by William James in Principles of Psychology (1890).7

The social self

Carr writes about this idea, placing Cooley’s looking-glass self alongside similar ideas of George Herbert Mead and Erving Goffman as extending James’s description of the social sources of the “I” and “me.” Instead of exploring this neglected concept as a basis for thinking about social change in the digital age, Carr ends the discussion by pointing out that Goffman’s conception of the self “was defined by in-person interactions in actual places—schools, offices, factories, homes, bars, churches, shops.” Carr then turns to Joel Meyerson’s No Sense of Place (1986) and its pessimism about the social effects of electronic mass media and online social spaces.

For Carr, the looking-glass self and other notions of the fundamentally social nature of human cognition have been abandoned for “the mirrorball self” of digital culture, “a whirl of fragmented reflections from a myriad of overlapping sources.” Social media have disappeared the ground beneath our collective feet, by “removing social interactions from the constraints of space and time and placing them into a frictionless setting of instaneity and simultaneity,” leaving us in an unreal social world that “vibrates chaotically to the otherworldly rhythms of algorithmic calculation.” This is insightful and impressive writing, but it ignores the ways that the medium’s message has always provoked a sense of disorientation among older people, and that social identity is always formed out of the materials and tools at hand.

It is true that digital social media pull us toward a disembodied and dislocated sense of self, but then so do many religious and cultural practices. In introducing his discussion of the self in Principles, James describes the way people are often “ready to disown their very bodies and to regard them as mere vestures, or even as prisons of clay from which they should some day be glad to escape.” He introduces the social self, along with the material self and the spiritual self, as a conceptual framework for making sense of the formation of individual identities. The social self gets all the attention, and is of obvious value in thinking about communication technologies, but our bodies and our relation to what James called “the higher universe” are merely forgotten in the moment, not lost completely, when our attention is subsumed by media.

I find Carr’s case for concern more convincing when he turns his attention to Silicon Valley’s “idealists with means,” who are looking to “give us a utopia of their own device, one that furthers their ethical and political as well as their commercial interests.” Carr has Marc Andreessen and Zuckerberg stand for the wider and wilder range of theories about this utopia, where we all become “virtual epicureans.” But we should not grant today’s postmodern feudalists too much originality. This is not our first crop of oligarchs with weird social ideas getting bent toward the right by their workers’ protests. When Henry Ford first began to engineer the automobilification of North America, he was optimistic about labor relations, but turned violently anti-labor and publicly anti-Semitic when it was apparent that workers had their own ideas about fair wages and working conditions. Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter echoes Ford’s purchase of his hometown newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, which became a vehicle for spreading anti-Jewish and anti-Labor conspiracies. At least so far, giant tech companies have not had their Pinkertons open fire or physically beat protesting workers.8

Despite the undeniable pull of screens and the immensity of the capital being deployed to capture our eyeballs, Carr too readily accepts the notion that we are lost to dopamine hits and digital toys. The recent habit of spending too much time on digital devices is like those charts beloved by tech investors, with lines that go up. Trends reverse. Habits change. Pretty screens and AI chatbots get boring. Attention may be captured, but our bodies and spirits persist, offering ground for a collective counter-friction to all the machinery Silicon Valley is desperate to sell us.

In Democracy and Education (1915), John Dewey writes, “The moving present includes the past on condition that it uses the past to direct its own movements.” People in the early decades of the last century faced a global rise in authoritarianism and a thrilling sense of possibility in new technologies, both sped along by waves traveling through the liquefying force of new social media. The political response to the pandemic of 1918, the Great Depression, and global wars did not solve our social problems, but it did create social safety nets that improved people’s material lives and civil rights movements that spoke to their spiritual longings.

Superbloom reminds us of the past but discounts its potential to direct us in the moving present. Dewey's The Public and Its Problems plays a role in Carr’s account of the past, but like so many who write about John Dewey’s exchange of ideas with Walter Lippmann in the 1920s, Carr misses the anti-technocratic projects Lippmann and Dewey collaborated on during this period and their shared belief that liberal democracy is the least worst answer to the problems of political organization in a social world shaped by globalizing capital and new social media.

Here is part two of this essay.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

The place to start is Cavell’s Carus Lectures in 1988, published as Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism. This tradition has its critics, most notably Hannah Arendt, who writes a letter to James Baldwin in 1962 saying that “love is a stranger to politics” and criticizes Thoreau's “Civil Disobedience” in an essay in the New Yorker in 1970, which is included in Crisis of the Republic (1972).

In this broad Earth of ours,

Amid the measureless grossness and the slag,

Enclosed and safe within its central heart,

Nestles the seed Perfection.

By every life a share, or more or less,

None born but it is born—conceal’d or unconceal’d, the seed is waiting

—Walt Whitman, Song of the Universal

For example, see How to Do Nothing (2020) by Jenny Odell.

Charles Horton Cooley: Imagining Social Reality (2006) by Glenn Jacobs. Cooley’s general neglect of race and gender helps explain his obscurity today. Like many academics of his day, his theoretical frameworks abstracted people into “mankind” and treated politics as something distinct from critical inquiry.

My take on Jesus is similar to Carr’s on Jaci Marie Smith, the social media influencer whose viral post about poppies blooming in Walker Canyon provides him with his title. The problems come from the actions of followers, not necessarily the actions and words of the original poster.

Check out Derek Thompson’s brief consideration of this question as applied to the two decades following 1900. Or, even better, read The Vertigo Years: Europe 1900-1914 by Philipp Blom, which is Thompson’s source.

Francis Galton set the framework for much of the theory and practice of the social sciences in the twentieth century. For a time, James’s ideas were quite influential, though he did not offer a methodology suitable for specialized graduate training. Ben Breen is working on a book project, Ghosts of the Machine Age, that promises to illuminate this contrast between Galtonian and Jamesian approaches to social science.

Figures like Cooley, James Mark Baldwin, John Dewey, W.E.B. Du Bois, and George Herbert Mead took James as a model for open-ended empirical inquiry, but, like James, none of them founded methodological schools. Walter Lippmann and Gertrude Stein were greatly influenced by James, too, and exercised their influence outside the academy through journalism and literature, respectively.

Then, there are the women who wrote and organized their way to prominence without the advantages of an academic appointment. Figures like Jane Addams, Anna Julie Cooper, Frances Harper, Lucy Sprague Mitchell, and Jessie Taft made significant contributions to social theory and practice while working as administrators, activists, and writers.

The fact that the government retains its monopoly on violence is not at all reassuring, given the actions of the current occupant of the White House. Yet, it is worth remarking that, for all their many faults, including their support for the current occupant and silence in the face of his dismantling the political economy that allowed them to become wealthy, the tech oligarchs do not typically employ violent thugs to beat protesting workers. I credit savvy media advisors more than their moral sensibilities, but the lack of violence compared to earlier eras is worth noting.

Looking forward to your Lippmann-Dewey take!