Five things I have learned writing AI Log + Phase 2 begins

AI Log turns two years old

The first edition of AI Log went live on August 25, 2023, with a LinkedIn post titled Five things you might have missed in AI news this summer. In those earlier days, I was trying to find a middle ground between the unrelenting hype of Silicon Valley and the unrelenting freakout among educators about ChatGPT. Two years later, those early posts read embarrassingly breezy. Eventually, I wrote my way to a more critical perspective on educational chatbots and found a more distinctive voice writing book reviews and essays about my experiments with LLMs in the classroom. I gave up hot takes and round-ups, though I still blow my top about the headlines on occasion.

My interest in writing long-form led to a change in platforms from LinkedIn to Substack, which, for now anyway, is ad-free. I also stopped using AI image generators. Behind those visible changes to AI Log was a shift in focus to longer-term social contexts for technological change, as I came to believe that the problems we associate with digital social media and AI models have roots going back hundreds and even thousands of years.

To celebrate this publication’s second anniversary, here are five things I discovered through writing AI Log.

Anthropomorphizing AI tools is a bad idea

Pretending chatbots are people has always felt problematic to me, which is why Ethan Mollick is one of my favorite writers about AI and education. He is the grand champion of anthropomorphizing AI models, the leading evangelist for the benefits of treating AI models as if they were human assistants and tutors. My opposition to thinking of AI as people was sharpened on the rock of Mollick’s vision of co-intelligence.

Recent stories about obsessive behavior have more people worried, but the Eliza Effect also interferes with understanding how transformer-based computational models actually work, and it blinds us to a wide range of ways we might put these computational algorithms that confabulate language to good purpose.

Large AI models are an educational technology

If Alison Gopnik and Henry Farrell are right that Large AI models are a cultural technology, then it follows that they are an educational technology. The question then becomes, what educational value do these tools offer? Instead of answering that question, mostly we talk about their social harms (there are plenty!) or speculate about what they might become (science fiction is fun!).

Understanding how large AI models function culturally and educationally is a path to moving beyond endless cycles of skepticism and speculation to think about how we might use these technologies to change educational institutions for the better. That path includes regulations to prevent companies from moving fast and breaking people and to break up monopolies, but it also means experimenting with generative AI models to try to accomplish socially beneficial goals. Here is a list of writers exploring AI as a cultural and social technology.

Large AI models are a normal technology

I use Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor’s framework in my public talks with educators and technologists because it focuses attention on where we are now with transformer-based AI models as the social process of innovation and diffusion plays out. Think about the history of major inventions like the railroad, telegraphy, electric generators, internal combustion engines, and the networked personal computer. It takes decades to learn what economic and social value a new technology offers—and understand the social problems each creates— because it takes a whole lot of people working together across many types of organizations to discover how new tools can be adapted and put to use. And then, it takes even more time to encourage people to adopt the tools.

Investors in technology companies desperately want this process to move faster than it does, which places pressure on the people who manage technology companies. But that’s their problem. Higher education has enough problems without borrowing those of Microsoft and OpenAI.

Spending millions on an enterprise contract with OpenAI or Anthropic feels like a bold move for a president or board to make. Less bold, and just as stupid, is paying Microsoft money for Copilot when there is no evidence that it adds value.

For all the seeming urgency of AI job training and AI literacy, it is still early days. We have a lot to learn about how AI will change the economy, organizations, and educational institutions, but treating AI as a normal technology will help us make better decisions.

Small is the next big thing

I try to avoid prognostication, but it seems pretty clear that the hype about the largest and latest AI models is fading. I wrote about what happens after the AI bubble earlier this summer. What will replace breathless coverage of how the latest releases perform on benchmarks or outrage over the latest disastrous attempt by some tech company to speed the commercialization of a product they don’t understand?

I hope it will be stories about smaller, open models solving medium-sized problems for organizations of all sizes. If generative AI is indeed revolutionary, I suspect it will come to feel boring, the way double-entry bookkeeping, the filing cabinet, and digital spreadsheets are boring.

Nineteenth-century ideas explain twenty-first-century technology

In 2024, I wrote several essays about how William James helps make sense of AI. I intended to follow up with similar pieces about two of his lesser-known contemporaries, Charles Sanders Peirce and Anna Julia Cooper, but I am a slow reader and even slower writer, especially when it comes to the history of ideas. Peirce makes a brief appearance in On Confabulation, which is my favorite essay on AI Log so far.

I quote Cooper in an upcoming review essay of Nicholas Carr’s Superbloom, which is largely about how the ideas of Charles Cooley and John Dewey make sense of today’s digital social media. I expect all five of these thinkers will figure in Phase 2.

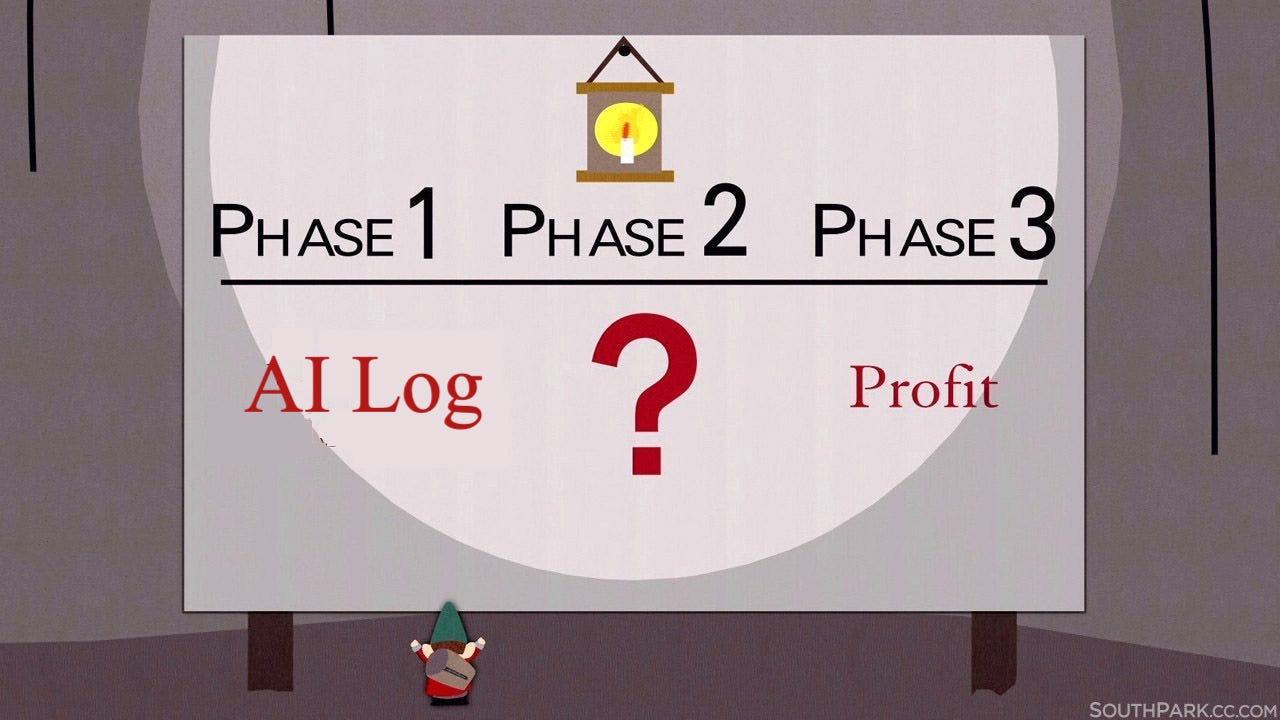

Phase 2 of AI Log

I wrote about Lizzie Douglas’s theory of cultural work in a market/attention economy in my review of John Warner’s More Than Words. You can hear the original formulation of her ideas here: I’m selling my pork chops, but I’m giving my gravy away.

AI Log is all gravy, but Phase 2 involves cooking up a pork chop with the working title of Solving for AI: Technology and the Future of Higher Education. I do not expect a book to get me anywhere near Phase 3, but there are other reasons to write, and ways to earn a living wage while writing.

I don’t turn on paid subscriptions to AI Log because I prefer to ride for free on this platform. That said, I could use your help in letting people know about that delicious AI Log gravy.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

Looking forward to phase 2 - agree with all these themes but the meat is, as you say, in how that transforms whole sectors like education